India Has Concerns Over Access to Bay of Bengal

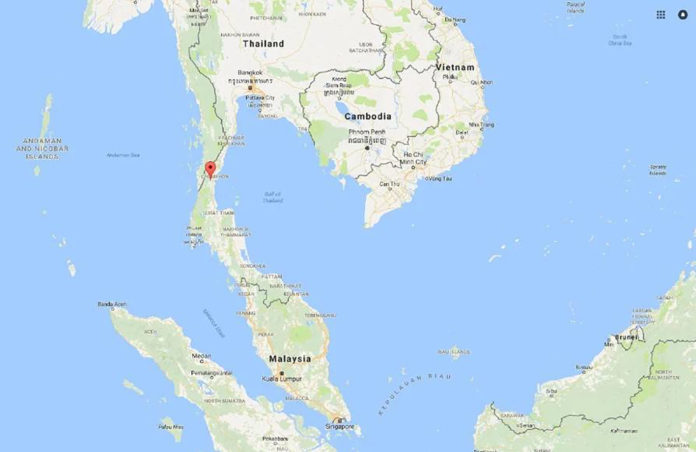

A Thai proposal to replace China’s relentless efforts to create Kra Canal project, which if implemented would give PLA Navy direct access to Bay of Bengal bypassing Malacca Strait, has been welcomed by India. India had expressed reservations over the proposed canal project as it could be threat to its security interests in the Bay of Bengal.

A canal across Thailand’s Isthmus of Kra would shorten its access to the Indian Ocean by 1,100 kms bypassing Malacca Straits. China has been apprehensive that its commercial tankers and Navy ships can be blocked by USA or regional countries in Malacca Straits. The Kra Canal would have been part of China’s “string of pearls” policy, including control over ports and potential naval bases in Cambodia and Sri Lanka.

Thailand has different plans to construct two deep seaports on both sides of the country’s southern coast, which would be linked via rail and highway – a 100 kilometre highway and rail passageway linking two seaports on either side of Thailand’s southern coast. This proposal replaces the Kra Canal plan.

Wiser about the canal’s inherent dangers, the Thai Transport Minister Saksayam Chidchob recently said he preferred building rail and highway links across the isthmus instead of a canal.

Kra Canal

The current Thai canal proposal, known as the 9A route, would involve two parallel channels—each 30 meters deep, 180 meters wide, and running 75 miles at sea level from Songkhla on the Gulf of Thailand to Krabi in the Andaman Sea.

Second Sea Route

A long-mooted canal across southern Thailand’s Kra Isthmus, the narrowest point of the Malay peninsula, which would open a second sea route from China to the Indian Ocean, could allow the Chinese navy to quickly move ships between its newly constructed bases in the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean without diverting more than 1000 kms south to round the tip of Malaysia.

The Thai canal could become a crucial strategic asset for China—and a potential noose around Thailand’s narrow southern neck. If Thailand allows China to invest up to $30 billion in digging the canal, it may find that the associated strings are attached forever.

Malacca Strait

The Malacca Strait has been a key corridor of global commerce for centuries, if not millennia. The Italian adventurer Marco Polo sailed through the strait in 1292 on his way home from the court of Kublai Khan. In the early 1400s, China’s Ming Dynasty admiral Zheng He passed through on his voyages to India, Africa, and the Middle East. Today, more than 80,000 ships a year transit the strait, which is a key corridor bringing oil to East Asia and manufactured goods back out. Modern Singapore’s prosperity has been built on its strategic location at the narrow southeastern end of the strait.

A quarter of globally traded goods use the Strait of Malacca. The current route through the Malacca Strait has almost reached its safe limit in terms of the shipping volume it can handle. Current alternatives to Malacca, like Indonesia’s Sunda Strait, would require east-west cargos to detour even further out of their way.

Chinese Submarines

Thailand is quietly but steadily pushing back against China by delaying plans to buy two Chinese submarines and expressing interest to replace Chinese proposal to build a canal in Bay of Bengal with its own project, a decision that could be welcomed in Delhi.

Thailand decided to delay, on 31 August, its $ 724 million purchase of two submarines from China, following public outrage over the controversial deal. Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha – also defence minister – “requested the navy to consider a delay” in the purchase of the two additional submarines.

Under a 2015 deal, Thailand had finalised its purchase of three submarines in 2017, with the first one expected to be delivered in 2023.

India’s Concerns

At sea, China is attempting to encircle India with a series of alliances and naval bases evocatively known as the string of pearls. China’s greatest vulnerability in its strategy to dominate the Indian Ocean—and thereby India—is the Malacca Strait, a narrow sea lane separating Singapore and Sumatra, through which so much marine traffic must pass that it’s both a lifeline for China’s seaborne trade and the main path for its navy toward South Asia, and points further west. With regards to China’s rivalry with India—and its strategic ambitions in Africa, the Middle East, the Mediterranean, and beyond—anything that reduces the dependency on one narrow chokepoint between potentially hostile powers is vital.

A Thai Canal would fit neatly into Beijing’s plans to encircle India. The Chinese Navy is actively pushing west into the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean, opening an East African logistics base in Djibouti and conducting joint exercises in the region with the navies of Myanmar, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Iran, and even Russia. The plethora of China-sponsored port infrastructure projects throughout the region only add to the impression of encirclement. India has responded by gearing up for potential future confrontations with China at sea.

India’s Counter Actions

India can effectively counter Chinese expansionism by upgrading its domestic forward bases and air and naval facilities in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, specifically to counter China. An Indian union territory with a population of fewer than half a million, the strategic archipelago intersects the sea lanes leading from the Malacca Strait into the Indian Ocean. They also have the potential to quarantine the proposed Thai canal.

Comments

The canal had gained widespread support among Thailand’s political elite. Chinese influence operations in Thailand probably helped shape public opinion.

The politically powerful Thai army argued that Thailand could divert some of that prosperity to itself, building industrial parks and logistics hubs at both ends of what could become one of Asia’s major transit arteries. But Thailand risks splitting itself in two with the proposed project. It has an active insurgency in its three southernmost provinces, which are majority Muslim in religion and majority Malay in ethnicity. The canal could become a symbolic border between “mainland” Thailand in the north and a separatist movement in the south. If Thailand were ever to break in two, the Thai canal could be the fault along which it cracks.

Colombia once had a northwestern isthmus called Panama. When Panamanian secessionists revolted in 1903, the U.S. Navy stepped in to ensure the new country’s independence. Panama has been a virtual U.S. protectorate ever since.

A successful Thai canal project would reconfigure the political geography of Southeast Asia. It would bring in China as a permanent security partner that could not easily be kicked out—just like Panama.

The real concern is that it would further undermine the independence of poor southeast Asian countries like Myanmar and Cambodia, which have comparatively weak civil societies that are highly vulnerable to Chinese interference.