Government Formation Exposes Divisions

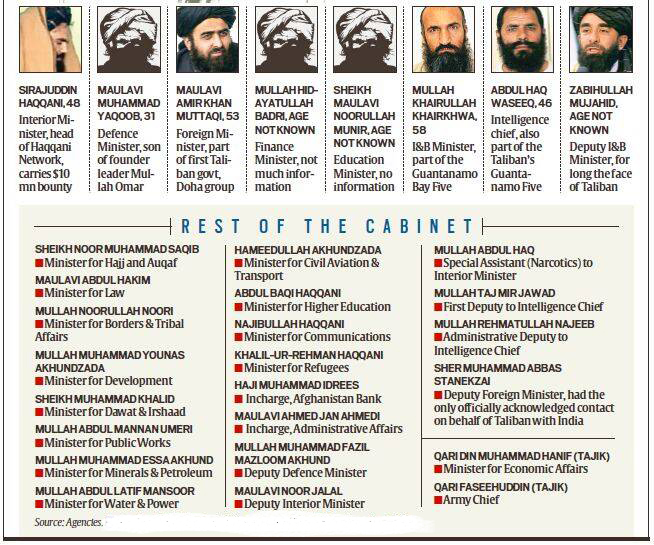

The Taliban, on 7 September, named Mullah Hasan Akhund, an associate of the movement’s late founder, Mullah Omar, as the new head of the government of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. No less crucial was the appointment of Sirajuddin Haqqani as interior minister. His organisation happens to be on the terrorism list of the United States of America. He is one of the FBI’s most wanted men because of his involvement in suicide attacks and ties with Al Qaida.

The US asserted in the immediate aftermath of the appointments that there would be no recognition of the Taliban government anytime soon.

The appointment of Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, head of the Taliban’s political office and one of the prominent negotiators at the serial conferences in Doha, as Prime Minister Akhund’s deputy, rather than to the top job, was more than a little surprising. Ever since 15 August, when the Taliban brought Kabul under its belt, he had been widely expected to be the next prime minister.

Baradar, once a close friend of Mullah Omar, was a senior Taliban commander in charge of attacks on US forces. He was arrested and imprisoned in Pakistan in 2010, and helmed the Taliban’s political office in Doha after his release in 2018. On the face of it, his claim to the PM’s office was strong, but as it has turned out it was Mullah Hasan Akhund who was eventually given the nod.

Mullah Mohammad Yaqoob, son of Mullah Omar, was named as defence minister in a series of ministerial appointments that were said to be in an “acting” capacity. To be tentative is the dominant strain.

The exclusion of women from the seat of authority was the other and unsurprising striking feature of the new dispensation. This rendered rather uncertain the support of a critical section in a profoundly theocratic country. The putative moderate face of the new regime was at a discount.

It is not clear what role in the government would be played by Mullah Haibatullah Akhundzada, the Taliban supreme leader. There was no indication that he would play the omnipotent role of Iran’s Ayatollah Khamenei. Islamabad’s fingerprints were visible in the new arrangement.

Haqqani Network

The Haqqani Network has emerged as the most powerful group in the new Taliban government, with four of the clan nominated as cabinet members.

The Haqqani Network takes its name from the leader of the group, Jalaluddin Haqqani, who first fought the Soviet Army in Afghanistan as a loyal ally of the CIA and the ISI, and then fought the US and NATO forces, while he led a protected existence in North Waziristan, where Pakistan gave him and the entire group safe haven.

Jalauddin’s death, in September 2018, was announced as having occurred of natural causes, although it was rumoured that he had died years before. The mantle passed to his son Sirajuddin.

Sirajuddin Haqqani, 48, is the new Interior Minister — an appointment that is a finger in the eye of the international community. He has been a UN-designated global terrorist since 2007, and the FBI has a reward of $10 million for information leading to his arrest. No recent photographs exist of him.

It describes him as “one of the most prominent, influential, charismatic and experienced leaders within the Haqqani Network… and has been one of the major operational commanders of the network since 2004. After the fall of the Taliban in 2001, Sirajuddin Haqqani took control of the Haqqani Network and has since then led the group into the forefront of insurgent activities in Afghanistan”.

According to the listing, he derived much of his power and authority from his father, Jalaluddin Haqqani — who was also listed, and described as “a go-between for al-Qaeda and the Taliban on both sides of the Afghanistan/Pakistan border”. Sirajuddin Haqqani was involved in the suicide bombing attack against a Police Academy bus in Kabul on June 18, 2007, which killed 35 police officers.

Haqqanis in Cabinet

Khalil-ur-Rahman Haqqani, the uncle of Sirajuddin, who has been appointed the Minister for Refugees, was listed as a terrorist in 2011. The listing says he travelled to Gulf countries, as well as in South and South-east Asia to raise funds on behalf of the Taliban and the Haqqani Network.

He is said to have been one of several people responsible for the detention of prisoners captured by the Taliban and the Haqqani Network. The listing links him to al-Qaeda as well.

Najibullah Haqqani, Minister for Communication, was listed in 2001. He had been a minister in the previous Taliban regime as well — first the deputy minister for public works, and later, deputy minister for finance. He was militarily active until 2010.

Sheikh Abdul Baqi Haqqani, an associate of Jalaluddin Haqqani and the new Minister for Higher Education, is the only leader of the Haqqani Network in the government who not designated by the UN Security Council. However, he has been sanctioned by the European Union.

On being appointed the shadow minister for education last month, he was reported as saying that while girls could study, “All educational activities will take place according to Shariah.”

Deep Roots in Af-Pak

Jalaluddin Haqqani, a Zadran tribesman from the Loya Paktia (Paktia, Paktika and Khost) area in eastern Afghanistan close to the border with Pakistan, was a member of the anti-communist, anti-Soviet Hizb-e-Islami, and became active as a mujahideen in the 1970s.

He is an alumnus of the Dar-ul-ulum Madrassa, also nown as the jihad factory, in Akhora Khattak in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

As the frontier of the Cold War came to Pakistan’s doors, he and several others were trained in Pakistan for jihad. When the Soviet Army arrived, he was among the CIA’s trusted mujahideen. Charlie Wilson, the US Senator who mustered money and weapons for the war, is said to have described him as “goodness personified”. During this time he forged deep ties with the ISI.

From a base in North Waziristan, Jalaluddin ran guns and fighters for the jihad all through the 1980s. This is also the time when he met Osama bin Laden in Miramshah, the headquarters town of North Waziristan. While he received largesse from the CIA and ISI, Haqqani is said to have also raised his own funds from wealthy sheikhs in Gulf countries, and during his annual Haj pilgrimage.

Haqqani joined hands with the Taliban in 1995, and he and his men fought alongside the Islamist movement against the various warring factions of the mujahideen.

When the Taliban captured Kabul in 1996, he became the Minister of Border and Tribal Affairs. The relationship between him and Mullah Omar was one of common interests, but it was hardly smooth, with Haqqani resentful of the prominence Mullah Omar gave to his inner circle from Kandahar.

After the ouster of the Taliban regime by the US and allied forces in 2001, the Haqqani family fled to Pakistan, where they are believed to have taken refuge in their old stronghold of Miramshah in North Waziristan.

They were said to be running a parallel administration there, taxing people and making money off construction contracts and investments in real estate in the area. Another source of income was from fund-raising in the Gulf.

Kidnapping for ransom was a major source of income, as was smuggling timber from Afghanistan into Pakistan.

In 2003, when the Taliban began regrouping, the Haqqani clan was central to their efforts. By then, Sirajuddin had taken over most of the operational aspects of the Haqqani Network from his father Jalaluddin.

Military observers credit much of the success of the Taliban to the Haqqani Network. The United States often urged Pakistan to “do more” to eliminate the Haqqani Network, but these efforts remained cosmetic.

The Institute for the Study of War report mentioned earlier says the Pakistani Army consistently refused to launch a military operation in North Waziristan despite the presence of the al-Qaeda’s senior leadership there.

Even while reporting directly to the Taliban Supreme Council, the Haqqani Network retained its own distinct identity.

Links with al-Qaeda, ISIS

As recently as May this year, a UN report described the Haqqani Network as “Taliban’s most combat-ready forces [with] a highly skilled core of members who specialize in complex attacks and provide technical skills, such as improvised explosive device and rocket construction….The Haqqani Network remains a hub for outreach and cooperation with regional foreign terrorist groups and is the primary liaison between the Taliban and Al-Qaida”.

The report, by the Taliban Sanctions Monitoring Committee, also noted that one member state had pointed to a link between the Islamic State-Khorasan Province (ISIS-KP) and the Haqqani Network, but the Committee itself was unable to confirm this. The link centred on the leader of the ISIS-KP, Shahab al-Muhajir, who “may also have been previously a mid-level commander in the Haqqani Network”.

An earlier report of the Committee had stated that “one Member State has suggested that certain attacks can be denied by the Taliban and claimed by ISIL-K, (same as the ISIS-KP) with it being unclear whether these attacks were purely orchestrated by the Haqqani Network, or were joint ventures making use of ISIL-K operatives”.

The 2008 Indian Embassy bombing in which a senior diplomat and a military official posted at the Embassy were killed among dozens others, mostly Afghan civilians, was blamed by US and Afghan intelligence on the Haqqani Network.

The National Directorate of Security, the intelligence agency of the erstwhile Afghan government, had provided communication intercepts to Indian authorities that pointed to Haqqani involvement, allegedly with ISI support. A similar claim was made by the CIA. Other reports pointed to a Lashkar-e-Taiba involvement, with support from the Haqqani Network.

The Haqqani Network is also said to have been behind the attacks on Indian construction workers in Afghanistan in the years 2009-2012. The group’s long relationship with and loyalty to the ISI make it an invaluable asset for Pakistan, according to security officials. There is considerable disquiet in the Indian security establishment that Sirajuddin Haqqani is a member of the new government of Afghanistan.