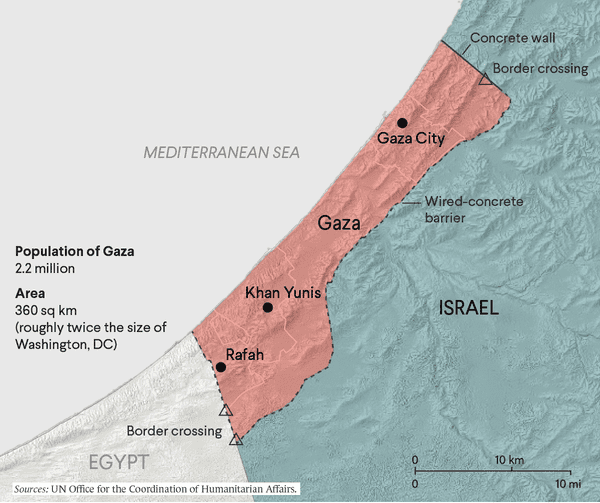

In 1948 the State of Israel was created on land inhabited by both Jews and Arab Palestinians. Hostilities between the two communities that year led to a mass displacement of Palest inians. Many of them became refugees in the Gaza Strip, a narrow swath of land roughly the size of Philadelphia that had come under the control of Egyptian forces in the 1948-49 Arab-Israeli war. The status of the Palestinians remained unresolved as the protracted Arab-Israeli conflict brought recurrent violence to the region, and the fate of the Gaza Strip fell into the hands of Israel when it occupied the territory in the Six-Day War of 1967.

In 1993 there was a glimmer of hope for a peaceful resolution when the Israeli government and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) reached an agreement on the creation of a Palestinian state alongside an Israeli state (see two-state solution; Oslo Accords). Hamas, a militant Palestinian group founded in 1987 and opposed to the more conciliatory stance taken by the PLO, rejected the plan, which included Palestinian recognition of the State of Israel, and carried out a terror campaign in an attempt to disrupt it. The plan was ultimately derailed amid suicide bombings by Hamas and the 1995 assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin by a Jewish extremist. In 2005, in the wake of the collapse of the peace process, Israel unilaterally withdrew from the settlements it had constructed in the Gaza Strip after 1967, and in 2007, after factional conflict within the Palestinian Authority (PA), Hamas emerged as the de facto ruler in the Gaza Strip. The takeover by Hamas prompted a blockade of the Gaza Strip by Israel and Egypt and set the stage for the next decade and a half of continued unrest.

The first major conflict between Israel and Hamas, which included Israeli air strikes and a ground invasion, took place at the end of 2008. Hostilities continued to break out, most notably in 2012, 2014, and 2021. Among the factors complicating those hostilities were the high population density of the Gaza Strip and the proliferation of subterranean tunnels there. Those tunnels were used by Hamas and other Gazans to sidestep the blockade, to conduct operations, and to hide from Israeli forces, and they were difficult to detect or destroy, especially when constructed under urban dwellings.

These conflicts were devastating for the Gaza Strip and came at a high human cost for Gaza’s civilians. But they usually lasted only weeks, resulted in few Israeli civilian casualties, and weakened Hamas’s military capacity. Hostilities often resulted in cease-fire agreements that temporarily eased Israel’s blockade and facilitated the transfer of foreign aid into the Gaza Strip. Many officials in Israel’s defense establishment maintained that Hamas had been effectively deterred by years of conflict and that an occasional flare-up of violence would be manageable. On October 7 the error of that assumption became tragically clear. Ongoing violence in the West Bank, political turmoil at home, and simmering tensions with Hezbollah in Lebanon were among the distractions that left Israel unprepared for the onslaught from the Gaza Strip.

ALSO READ: EDITORIAL – The Hamas Terrorist Attack of 7 October

In early 2022 militants from the PIJ and new, localized groups in the West Bank, a territory northeast of the Gaza Strip that is also predominantly inhabited by Palestinians, conducted a string of attacks in Israel. The IDF responded with a series of raids in the West Bank, resulting in the deadliest year for the West Bank since the end of the second Palestinian intifada (uprising; 2000-05). The IDF targeted PIJ militants in the Gaza Strip-but left Hamas alone. In turn, Hamas refrained from escalating the conflict, bolstering the assumption by Israeli officials that they could prioritize other threats over Hamas.

At the close of 2022, Benjamin Netanyahu returned to office as Israel’s prime minister after cobbling together the most far-right cabinet since Israel’s independence, which proved to be domestically destabilizing. The cabinet pushed for reforms to Israel’s basic laws that would bring the judiciary under legislative oversight; the polarizing move led to unprecedented strikes and protests by many Israelis, including thousands of army reservists, concerned over the separation of powers. In August 2023 senior military officials warned lawmakers that the readiness of the IDF for war had begun to weaken. All the while, provocations by Hezbollah were raising the risk of conflict along Israel’s northern border.

But while tensions were brewing at home, Saudi Arabia-which had long conditioned diplomatic relations with Israel on the conclusion of the Israeli-Palestinian peace process-had begun negotiating with Israel and the United States on an Israeli-Saudi peace deal. Although Saudi Arabia sought concessions on issues related to the Palestinians, the Palestinians were not directly involved in the discussions and the deal was not expected to satisfy the grievances of the Palestinians in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Many observers believed that disrupting those negotiations was one of the goals of Hamas’s October 7 attack.

That deal was part of a broader regional transformation. The United States, which had long been the driving force behind the peace process, sought a “pivot to Asia” in its foreign policy and hoped an Israeli-Saudi deal would reduce the resources it needed to devote to the Middle East. Iran, meanwhile, was consolidating an “axis of resistance” in the region that included Hezbollah in Lebanon, Pres. Bashar al-Assad in Syria, and Houthi rebels in Yemen. Hamas, whose relationship with Iran had been tumultuous in the 2010s, had grown closer to Iran after 2017 and received significant Iranian support to build up its military capacity and capability.

On October 7, 2023, Hamas led a stunning coordinated attack, which took place on Shemini Atzeret, a Jewish holiday that closes the autumn thanksgiving festival of Sukkot. Many IDF soldiers were on leave, and the IDF’s attention had been focused on Israel’s northern border rather than on the Gaza Strip in the south.

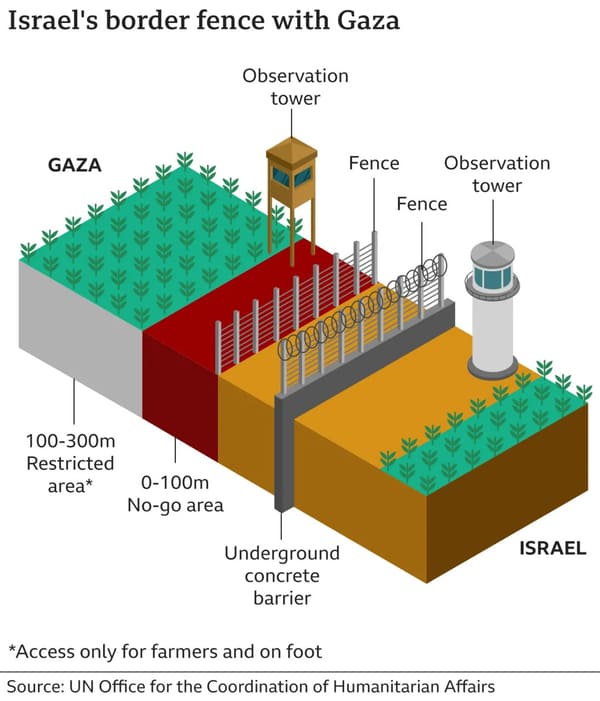

The assault began about 6:30 AM with a barrage of at least 2,200 rockets launched into Israel in just 20 minutes. During that opening salvo, Hamas used more than half the total number of rockets launched from Gaza during all of 2021’s 11-day conflict. The barrage reportedly overwhelmed the Iron Dome system, the highly successful antimissile defense system deployed throughout Israel, although the IDF did not specify how many missiles penetrated the system. As the rockets rained down on Israel, at least 1,500 militants from Hamas and the PIJ infiltrated Israel at dozens of points by using explosives and bulldozers to breach the border, which was heavily fortified with smart technology, fencing, and concrete. They disabled communication networks for several of the Israeli military posts nearby, allowing them to attack those installations and enter civilian neighborhoods undetected. Militants simultaneously breached the maritime border by motorboat near the coastal town of Zikim. Others crossed into Israel on motorized paragliders.

ALSO READ: US-Iran Rivalry : Can Iran Crisis Lead to a Wider War?

About 1,200 people were killed in the assault, which included families attacked in their homes in kibbutzim and attendees of an outdoor music festival. That number largely comprised Israeli civilians but also included foreign nationals. A March 2024 United Nations report found evidence that some were victims of sexual violence before they were killed. Adding to the trauma was the fact that it was the deadliest day for Jews since the Holocaust.

More than 240 others were taken into the Gaza Strip as hostages. Many of them were taken from their homes and some from the music festival. Including Israelis with dual citizenship, more than half of those taken hostage collectively held passports from about two dozen countries, effectively pulling several countries into the efforts to release their citizens.