According to British documents, “after the war arisen between Honourable East India Company and the Rajah of Nipal’, the Treaty of Segowlee or Sigauli/Sugauli, December 2, 1815, between Nepal and the British, was received from the Rajah of Nipal on March 4, 1816, and approved by him on December 8, 1816.”

The treaty, signed by Lt Colonel George Ramsay, for Charles John Earl Canning Viceroy and Governor-General of India and by Maharaja Jung Bahadur Rana for Maharaja Dheraj Soorinder Vikram SahBahadoorShumsher Jung was sealed at Kathmandu on November 1, 1860, and ratified at Calcutta on November 15, 1860.

A significant development of this treaty was the emergence of the Gurkhas of Nepal highland, as they were recruited into the nascent British Indian Army and given the pride of place on a par with, if not superior to, recruits from the “hinterland of Hindustan.” Thus, an ‘alien’ homogeneous ethnic combat Gurkha Regiment was born to be the prima donna of Indian military in no time, thereby setting an unprecedented change in the war machine structure of South Asia. Tribal hillmen from the Nepal Himalayas became integral and an inalienable part of the folklore of India’s military operations from Hindustan to Han land; Meerut to Mesopotamia; Aliwal to Ardennes; and, Lucknow to Libya for over 200 years now.

“In fact, so pleased were the handful of part-time English trader-cum-aspiring rulers — lording over part of Hindustan heartland — with the Kathmandu king, that they concluded a second treaty with him in November 1860. It thus elaborated: ‘During the disturbances which followed the mutiny of the Native army in Bengal in 1857, the Maharajah of Nipal not only faithfully maintained relations established between the British Government and State of Nipal by the Treaty of Sugauli, but freely placed troops at the disposal of British authorities for preservation of order in frontier districts, and subsequently sent a force to cooperate with the British Army in the recapture of Lucknow and final defeat of the rebels. On conclusion of these operations, the Viceroy and Governor-General, in recognition of the eminent services rendered to the British Government by the State of Nipal, declared his intention to restore to the Maharajah the whole of lowlands lying between the Kali river and the district of Gorukpore, which belonged to the State of Nipal in 1815, and were ceded to the British Government in that year by the aforesaid treaty of Sugauli.”

Significantly, as can be found from the language of both Nepal-British treaties pertaining to Indian territories lying to the west of the Kali river, there is neither any ambiguity nor dispute that these have been with India. The British were fighting a sovereign Nepal, ostensibly on behalf of a dependent India of several scattered indigenous rulers and battered princes. Nepal, therefore, could be seen as an aggressor of Indian soil, like the British, in the 19th century. Hence, it was clearly a fight between two foreign powers — British and Nepal — for parcelling out Indian soil in the 19th Century.

India, thus, inherited the boundary with Nepal, established between Nepal and the East India Company in the Treaty of Sugauli in 1816.

Kali river constituted the boundary, and the territory to its east was Nepal. The dispute relates to the origin of Kali.

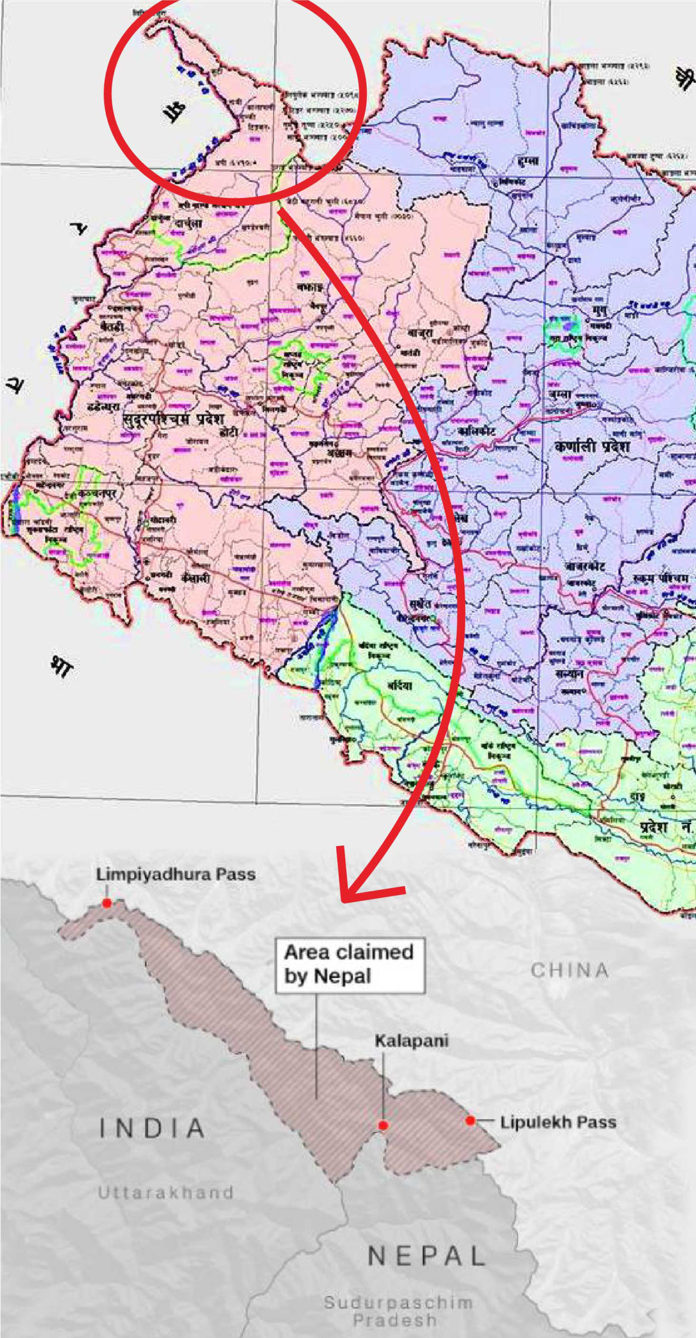

Near Garbyang village in Dharchula Tehsil of the Pithoragarh district of Uttarakhand, there is a confluence of different streams coming from north-east from Kalapani and north-west from Limpiyadhura. The early British survey maps identified the north-west stream, KutiYangti, from Limpiyadhura as the origin, but after 1857 changed the alignment to Lipu Gad, and in 1879 to Pankha Gad, the north-east streams, thus defining the origin as just below Kalapani. Nepal accepted the change and India inherited this boundary in 1947.

The Maoist revolution in China in 1949, followed by the takeover of Tibet, created deep misgivings in Nepal, and India was ‘invited’ to set up 18 border posts along the Nepal-Tibet border. The westernmost post was at Tinkar Pass, about 6 km further east of Lipulekh. In 1953, India and China identified Lipulekh Pass for both pilgrims and border trade. After the 1962 war, pilgrimage through Lipulekh resumed in 1981, and border trade, in 1991.

Kalapani, a patch of land near the India-Nepal border, close to the Lipulekh Pass on the India-China border, is one of the approved points for border trade and the route for the Kailash-Mansarovar yatra in Tibet.

In 1961, King Mahendra visited Beijing to sign the China-Nepal Boundary Treaty that defines the zero point in the west, just north of Tinkar Pass. By 1969, India had withdrawn its border posts from Nepali territory. The base camp for Lipulekh remained at Kalapani, less than 10 km west of Lipulekh. In their respective maps, both countries showed Kalapani as the origin of Kali river and as part of their territory. After 1979, the Indo-Tibetan Border Police has manned the Lipulekh Pass. In actual practice, life for the locals (Byansis) remained unchanged given the open border and free movement of people and goods.

After the 1996 Treaty of Mahakali (Kali river is also called Mahakali/Sarada further downstream) that envisaged the Pancheshwar multipurpose hydel project, the issue of the origin of Kali river was first raised in 1997. The matter was referred to the Joint Technical Level Boundary Committee that had been set up in 1981 to re-identify and replace the old and damaged boundary pillars along the India-Nepal border. The Committee clarified 98 per cent of the boundary, leaving behind the unresolved issues of Kalapani and Susta (in the Terai) when it was dissolved in 2008. It was subsequently agreed that the matter would be discussed at the foreign secretary level. Meanwhile, the project to convert the 80-km track from Ghatibagar to Lipulekh into a hardtop road began in 2009 without any objections from Nepal.

The Survey of India issued a new political map (eighth edition) on November 2, 2019, to reflect the change in the status of Jammu & Kashmir as two Union Territories. Nepal registered a protest though the map in no way had changed the boundary between India and Nepal. However, on 8 November, the ninth edition was issued. The delineation remained identical but the name Kali river had been deleted. Predictably, this led to stronger protests, with Nepal invoking foreign secretary-level talks to resolve issues.