Modern day warfare is no longer constricted to military face-offs across borders, territorial annexations and fighting foreign interventions. With the swell of globalization the nation states’ increasing quest has been to boost their presence in other sovereign territories, not as colonizer in its true sense, but as economic giants and investors. Though many term this as neo-colonizers, the trend has shifted the dominant narrative of security from territorial to more supra-territorial or to put it in a better term, trans-territorial. However, this has not really ebbed the importance of a country’s military might, it has rather diversified its role, compelling nation-states to fortify their presence in various layers of the polity that ranges from territorial to socio-economic security. As more commercial methods replace military methods, the ideas of existential threat are becoming more variegated. It is now quite understandable that economic disparities are giving rise to non-state actors like terrorists and insurgents but at the same time one cannot deny that the craving to expand a country’s influence beyond its borders have made nation-states even bigger threats, not for waging a direct war but playing a stake to instigate political upheavals disrupting the law and order machinery of their rivals.

Ensuring untethered flow of goods, commodities and energy imports have become the priority, thus, the notion of security has shifted from protecting the land territories to securitizing the Sea Lanes of Communication (SLOC). In this age of globalization, a country’s energy reserves determine its relative power, thus, SLOCs today have become the backbone of any nation’s economy. Almost, two-third of every country’s oil imports pass through oceans and seas. Moreover, countries today relentlessly strive to secure their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) and the reservoirs of marine resources from foreign interventions. This growing importance of oceans in terms of geo-economics has reconstructed marine spaces as zones of contestation and conflict, where most powerful nations of the globe have begun to make their naval presence felt, thereby, making the overall role of navies more imperative than ever before.

The Case of Indian Ocean

Indian Ocean that theoretically extends from the east coast of Africa and continues up to the west coast of United States includes world’s most important oil trade routes as it connects the major oil exporting countries in the Persian Gulf near the Horn of Africa and also incorporates the natural gas reserves of Myanmar in Bay of Bengal. The SLOCs that passes through the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) carry almost two-third of world’s oil trade, one-third of cargo and one-half of world’s container traffic. The immense geo-economic importance of the IOR has made it a zone of geopolitical tiff between US, Australia, Japan and China. The idea is to protect the sea lanes and the EEZs. The major threats of the IOR, however, are not restricted to conventional state-centric naval confrontations. Non-traditional factors have emerged, such as, resilience of pirates in red seas, small arms and narcotics trade from the Golden Crescent and Golden Triangle, human trafficking and maritime mixed migration (that takes the path from Horn of Africa through the Mediterranean Sea including the cases of Rohingyas from Myanmar), climate change and disasters in the Bay of Bengal (which remains the hotbed of tropical cyclones) and the illegal, unreported, unregulated fishing in the EEZs of the littoral countries.

The Emerging Zone of Conflict

With this changing dynamics of the IOR region, along with the persistent maritime territorial conflicts and naval power projections by the major players, IOR has emerged as a zone of two dominant rivalries. One, in the South China Sea where the conflict is between China and the United States, which is the net security provider for the South East Asian countries like Vietnam and Philippines.

The contest is on two fronts; One, annexation and subsequent protection of Spartly, Parcel Hainan and Zhongsha archipelago and Second, to ensure that China fails to dominate the SLOCs that pass through the Malacca Strait.

The other zone of scuffle remains the Bay of Bengal-Arabian Sea-Indian Ocean Tri-Junction that overlooks the Indian Peninsula. Sino-Indian conflict that gets exposed in this zone is delineated by

• India’s shoring efforts to counter China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) along with port developments in the littoral countries and China’s attempt to develop one.

• A Two Ocean’s Strategy, whereby China can bypass the Malacca Strait for its oil trade and to implement the Maritime Silk Road Initiative (MSRI) by investing in the infrastructural development of the island countries in the IOR.

With China recognized as the pre-eminent threat in the IOR, it becomes implausible to go into further exploration of the region without estimating Chinese footsteps in IOR. For Beijing, Indian Ocean has served as its dominant source of energy. Eighty percent of China’s total oil imports pass through the Indian Ocean and primarily the Malacca Strait. China’s launch of MSRI and BRI is just an attempt to secure and ease its oil importing routes be they land or maritime and, to some extent, avoid the Malacca Strait chokepoint. Thus, in order to secure these ambitions, China is proliferating the presence of People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) by deploying 31st Task Force of PLAN in the IOR. China’s has set up military bases in Djibouti, Jiwani Peninsula near Gwadar, listening port in Coco Islands near Myanmar, apart from developing ports in Sri Lanka, Maldives and Bangladesh.

India’s Indian Ocean Strategy

Constricted to protecting the northern land frontiers, India’s security predicaments post-Independence were dominated by her brawl with Pakistan and China. However, India never underestimated her stake in Indian Ocean. Since independence, India visualized her role as the ruler of the waves in order to proliferate her influence in the region, thereby, propping up her naval presence in the IOR. In the 1960s, the Indian Navy was allocated only 4 per cent of the total defence expenditure of the country. Today, Indian Navy enjoys 15 per cent of the total defence budget (US$ 66.9 for 2020-21), although it still remains lower than other two sectors – Army and Air Force. India’s role has largely been that of ‘Security Provider’ to ensure that the IOR remain a zone of neutrality with no power having hegemony over it. However, the emerging pockets of intimidation, the threat posed by terrorists in the aftermath of 26/11 Mumbai attack, coupled with India’s ambition to become the dominant regional leader, has lured India to flex her muscles, both by taking a soft power posture through its outreach programmes and investments and by proliferating joint naval exercises with other powers in the region. The IOR, now considered as the Greater Indo-Pacific, is witnessing new areas of cooperation, where India has been included in the ‘Quadripartite Alliance’ with US, Japan and Australia to cooperate on naval patrolling to ensure overall security in the ocean. Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) and India Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS) New Delhi have hosted naval exercises with Vietnam and trilateral Malabar exercises with US, Japan and Australia. India today is US’s major defence partner in safeguarding the South China Sea. In the soft power domain, India SAGAR (Security And Growth for All in the Region) has brought India closer to the littoral islands that includes Maldives, Seychelles and Eastern African countries of Mauritius, Madagascar and Comoros.

Strategic Deterrence or Calculated Belligerence?

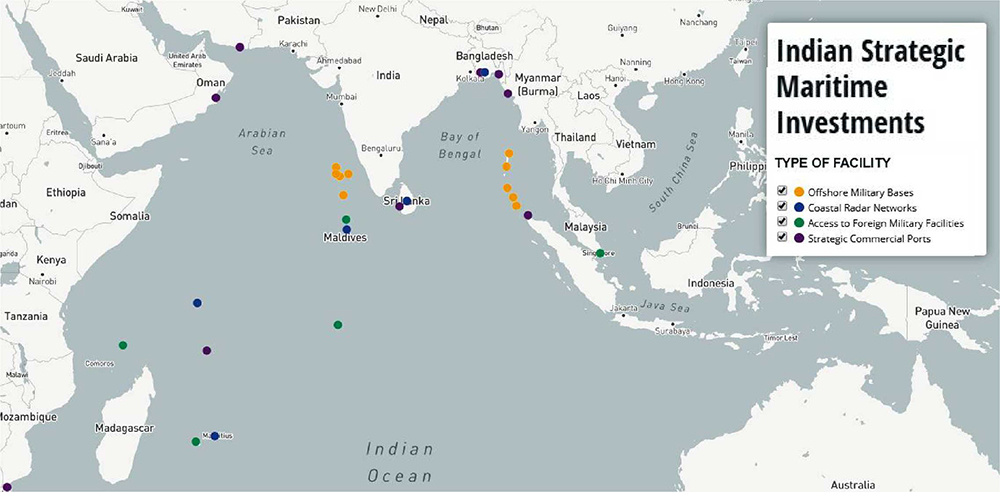

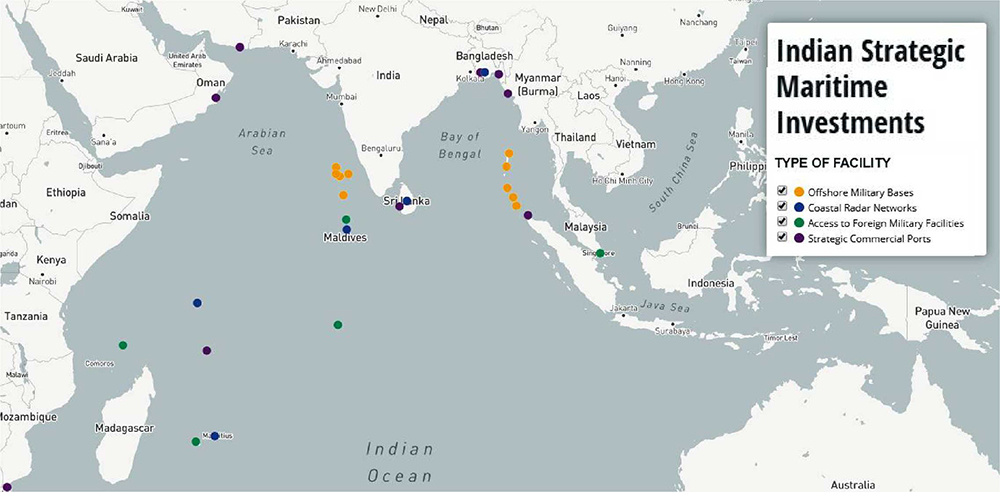

There are two extreme postures that India can take to strategize the IOR; one; a defensive posture to deter threat and contain further proliferation of foreign navies in the region and second, enhancing its own capabilities to become a maritime power to control the waves, flex its power and boost its presence. However, India has taken up a posture that includes the element of both and here the role of the Indian Navy has become crucial. Indian Navy today possess a mix of aircraft carrier, destroyers, frigates and patrolling vessels. Although it currently possess 130 warships, 20 aircrafts, 24 attack submarines and a nuclear ballistic missiles submarine (Arihant), under the modernization process within the Maritime Capabilities Perspective Plan (MCPP) it will increase its capabilities to 200 ships, 500 aircrafts and 24 attack submarines by 2027. Apart from enhancing maritime capabilities, India has begun chessboard diplomacy in the IOR. Today, in order to counter Chinese port investments, India has begun to expand her presence by developing deep sea ports in Sitwe, Myanmar and in Sabang, Indonesia that position India close to the Malacca Strait. India’s ambitious Chabahar port project in Iran and port access in Duqm, Oman again place her in the backyard of Chinese presence in Gwadar. India, by now, has already established surveillance radars in Mauritius, Madagascar, Seychelles, Oman, Maldives and Sri Lanka with proposals to build a military base in Seychelles and a listening post in Cocos Island, Australia. In order to counter non-traditional security threats, the Indian Navy is working towards calibrating its capacity in Big Data analysis and Artificial Intelligence.

Way Forward and Challenges Ahead

Sino-Indian and Indo-Pak rivalry has remained the pre-dominant threat in the narrations of India’s security doctrine. With the 26/11 Mumbai attack, India’s idea of protecting her frontiers has increasingly included maritime routes as well. However, for China the calculations are tumultuous. It is important to understand that China’s territorial incursions in Ladakh are just to ensure that its China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is safe at the time when India has escalated her control over the region. One also cannot deny that China’s ‘Middle Kingdom’ ideology is another determining factor, but the fruits of globalization have ultimately made it important for powers like China to secure her energy import routes. Therefore, there is no doubt that with the completion of China’s BRI, Sino-India rivalry will gradually shift more towards the IOR. The competition that unravels in the region, is about exacting the confidence of small independent littoral countries that are situated in the orbit of the SLOCs. Thus, for India the struggle is multidimensional and there are four imperatives:

• Safeguarding her own maritime frontiers from foreign, specially Chinese incursions.

• Ensuring regional consolidation and multilateral cooperation in emerging areas of mapping continental shelf, hydrography, blue water economy and joint naval exercises.

• To make its defence capabilities available to small independent states that will provide India geo-advantages on two fronts namely, power projection and expansion of influence.

• To continue with its chess board diplomacy, whereby Indian Navy’s enhanced role as pawns to hinder Chinese inroads is ensured.

Although, a plethora of literature is emerging that analyses the construction of artificial islands, construction of such entities – whether targeted towards India and China – will be opposed in lieu of safeguarding sovereignty. As for challenges, it is the declining budget allocation and lack of resource prioritization for the Navy, coupled with the huge disparity between Indian Navy’s capacities and its current capabilities. But it is high time for realizing that, given the changing dynamics of warfare that is stimulated by the currents of globalization, it is the Navy that will form the future backbone of India’s security. As long as geo-economics continues to define the trends of geo-politics, the Indian Ocean will continue to remain a zone of conflict. It is for our nation to decide how it strategizes the space in which it enjoys the most advantageous cartographical position.