Successive political establishments in Nepal have been tempted to play the China card against New Delhi, exploiting the former’s rivalry and disputes to its advantage.

Days before prime minister KP Sharma Oli came up with a new map of Nepal effectively committing cartographic aggression against India in the Kalapani area, his weakening domestic political situation and challenge from senior party leaders was defused after China mediated a deal between the leaders. Some days before the crucial meeting of Nepal Communist Party, Chinese Ambassador Hou Yanqi held a series of meetings with its senior leaders. Beijing made its concern clear that the ongoing strife within Nepal’s ruling coalition was not in China’s interests, since it had invested heavily in Nepal and needed Kathmandu to create as many pin pricks for New Delhi as possible.

The rift and Oli’s own nationalist politics, which seem to disappear when it comes to China, and domestic political opinion resulted in Kathmandu taking a strong position on the question of territory.

If there were any doubts about the Chinese investment in the NCP and backing for Oli, they was dispelled.

In the “Great Game” of politics in Nepal, Beijing demonstrably has an upper hand and has displaced India. During the pre-2006 people’s revolution and civil war periods, Chinese diplomats in Kathmandu, deviously claimed that Beijing did not interfere in any country’s internal affairs. They would describe the Maoists as hijackers of Mao’s name. But after the Maoists came to power in 2008, Beijing conveniently discovered ideological identity and congruity with them.

Sino-Indian Border Differences

Borders of most of India’s northern states of Ladakh, Himachal, Uttarakhand, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh contiguous to China have disputes and have heavy military deployments on both sides. In addition, there is a major dispute between India and China over the road built by the latter to reach Pakistan under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project. In 2017, China also made an attempt to ingress into Bhutan in the Doklam area. India was compelled to make its military presence felt strongly.

China has never raised any objections to India building a road to Lipulekh and opening the route to Mansarovar. When India proposed the opening of the Lipulekh Pass roadway, it appealed to China since it fulfilled its economic imperatives and aspiration to reign supreme in the India market.

India and China do not have a claims or dispute over territory in the Lipulekh region that Nepal claims as its territory. China has no deployment there, but India does. Hence, this area became a convenient area for the two countries to connect via road. The lack of geographical barriers also made the route a less circuitous alternative.

The new route reduces the distance from Delhi to the India-China border. From the Indian town of Pithoragarh through Lipulekh the distance by road is about 170 kms.

The direct road allows India to import Chinese goods at a cheaper rate and export its products to China easily. In 2019, India’s trade deficit with China was about US$54 billion. With the newly built road, India wants to export its products to China and reduce the trade deficit.

China’s Message

From a stand-off between the soldiers of the two countries at Naku La in North Sikkim on 8 May 8 to Pangong Tso lake, Demchok and other places in Ladakh, China has displayed aggressiveness at the tactical level, though at the strategic level the relationship with India remains stable.

These incidents are not unconnected. Chinese military actions are not random. They are well thought through. The Chinese military is part of the political establishment.

Covid-19, the disease bought on by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, has isolated China across the world stage, with many countries pressing for an independent probe into the origins of the virus from Wuhan.

Actions by Kathmandu, and the Chinese confrontation with India is part of subtle messaging to India not to lend its voice to the growing clamour against China.

China has created a three-pronged headache for India.

• The China-origin virus, which has already shattered all hopes of India’s goal of $5-trillion GDP by 2023-24.

• The political-diplomatic headache originating from Kathmandu.

• The muscle-flexing by People’s Liberation Army (PLA) attacks on Indian soldiers in Ladakh’s Galwan valley, Daulat Beg Oldi sector, and Naku La in Sikkim.

China in Nepal

In the past, China was interested in keeping a tab on the Tibetan refugee community in Nepal. With the abolition of the monarchy, China shifted attention to the political parties as also to institutions like the Army and Armed Police Force. Today China considers Nepal an important element in its growing South Asian footprint.

A lull in relations between India and Nepal for the past 17 years gave an opportunity to China to step up its engagement with Kathmandu through massive investments. After the 2015 India-Nepal rift, China amplified its political and economic investments in Nepal.

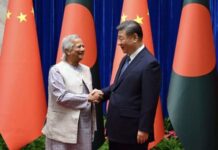

In October 2019, Chinese president Xi Jinping made a two-day visit to Nepal, becoming the first Chinese President in more than two decades to visit Nepal. During the visit, significant deals were inked to include a rail link connecting Tibet with Kathmandu. A road tunnel was also proposed to bring Kathmandu and the Chinese border closer. The Nepal-China Transit protocol was signed to counter the India-Nepal international trade interests.

Resentment Against China

All is not well between China and the Nepalese. China’s growing activities in Nepal have caused some unease in the country and the government. This is also reflected on social media. Chinese efforts to propagate its belief, culture and projects in Nepal, which includes moves to popularise Mandarin language to increasingly cornering local small and micro-enterprises has not gone down well. Local traders are feeling the heat due to Chinese presence.

Resentment against China, at the administrative level, can be discerned around the slow progress of the mega projects to be built by Chinese companies under its Belt and Road Initiative.

Kathmandu had accepted nine of the 35 projects proposed by China including the Kathmandu-Kerung Railway that alone is estimated to cost at least $2.3 billion, which is about 10 per cent of Nepal’s GDP. The utility of the railway line, which has been projected to end Nepal’s dependence on India for supplies, has been questioned.

While Bangladesh, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Maldives have been in pursuit of balancing Indian and Chinese economic, political and strategic interests, Nepal has had difficulty stabilizing these influences, resulting in acute insecurity and instability over the last several years.

For Nepal, Lipulekh is a tricky and prickly issue, since both India and China do not see it as a dispute between the two. Yet, there is a nagging suspicion that China has turned a blind eye to Nepal raising the stakes through a notification in Nepal’s parliament on 20 May.

Comments

India’s decisions around Article 370, on 5 August 2019, steps to increase border security, an image of assertiveness against Pakistan has Beijing taking notice as any gain in India’s image will be counterproductive to furthering its own influence in South Asia. China has emerged more successful in challenging and even dislodging India from its influential pedestal in the South Asia. But Nepal is still within the India’s sphere of influence.

Beijing has stepped up its never before seen brash diplomacy to chase its global goals. From Kabul to Colombo, Male to Myanmar, Thimpu to Kathmandu, India faces the long shadow of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in areas as diverse as territory to trade, telecommunications to terrorism and tourism to technology.

For the last several years, countries like Nepal, Maldives, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Afghanistan have in effect become playgrounds for great-power competition between these two countries. Whether it is the internal political dynamics, investment or cultural influence, the two countries have vigorously jockeyed to expand their influence while negating or diminishing each other’s influence across the South Asian region.

The Chinese aim is to command and control vast water resources and reservoirs of the entire Himalayas – the virtual lifeline for more than 1.8 billion people of South Asia.

At the backdrop of Beijing’s current diplomatic setback at the global fora, China will intensify its offensive in South Asia, the Pacific and Indian Ocean to project its power.