India and the US, on 15 September 020, signed a statement of intent (SoI) to strengthen the bilateral dialogue on defence technology co-operation and create opportunities for co-production and co-development of military equipment. The statement was signed by Raj Kumar, secretary, defence production, Ministry of Defence, and Ellen Lord, US under secretary of defence for acquisition and sustainment, during the 10th Defence Technology and Trade Initiative (DTTI) Group Meeting that was held virtually.

The aim of the DTTI Group is to bring sustained leadership focus to the bilateral defence trade relationship and create opportunities for co-production and co-development of defense equipment. Four joint working groups focused on land, naval, air and aircraft carrier technologies have been established under DTTI to promote mutually-agreed projects within their domains.

Since the last DTTI Group meeting in October 2019, a DTTI Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for the identification and development of cooperative projects under DTTI has been completed. The SOP will serve as the framework for DTTI and allow both sides to reach and document a mutual understanding on how to define and achieve success.

Background

Earlier, the US and India had signed a “Joint Statement of Intent” (SoI), on 24 October 2019, that formalised their intention to co-develop a range of cutting-edge warfighting technologies and systems for their militaries.

ALSO READ: INDIA – U.S.: Indo-US Defence Cooperation Enters New Phase

The agreement for all practical purposes superseded the six co-development projects announced in 2015, but which were never concluded, under the US-India DTTI. DTTI was a narrow, government-focused approach. Both sides have realised that joint development projects should be piloted by defence industry on both sides, while the Pentagon and Indian Ministry of Defence (MoD) oversee progress and deals with regulatory roadblocks that may arise.

DTTI Forum

Seven American and 20 Indian defence firms attended the new “DTTI Industry Collaboration Forum”, where the agreement and the DTTI Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) was signed on 25 October 2019.

The DTTI Industry Collaboration Forum will provide a standing mechanism for developing and sustaining an India-US industry dialogue on defence technological and industrial cooperation and to allow appropriate industry recommendations to be provided to the India-US DTTI Group.

In addition, the DTTI SOI, declared the joint intent to “strengthen our dialogue on defence technology cooperation by pursuing detailed planning and making measurable progress” on several specific DTTI projects.

ALSO READ: Editorial: Towards a Comprehensive Indo-US Strategic Partnership

The SOP will help identify and develop cooperative projects under DTTI, allowing both sides to reach and document a mutual understanding on how to define and achieve success.

New Projects

Projects which have been dropped from the 2015 DTTI list include:

• Co-development of Raven micro-UAS.

• Mission-specific interiors for C-130J Super Hercules aircraft.

• A mobile electric-hybrid power source.

• Protective clothing for soldiers in a nuclear contaminated battlefield.

During the 24 October DTTI meeting, both nations agreed to co-develop three specific projects in the near-term, two in the mid-term and two long-term projects. Lord clarified that “near-term” meant about six months.

Near Term. Near term projects agreed were:

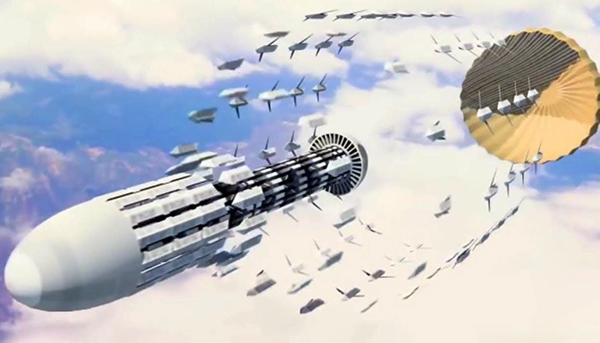

• Air-launched unmanned airborne systems (UAS), which is a drone swarm that is launched from an aircraft to overwhelm enemy defences.

• Intelligence, surveillance, targeting and reconnaissance (ISTAR), which is command and control software that enables coherent battlefield command.

• Light weight small arms technology involves building rifles, carbines and machine guns from lightweight polymer cast material with light-weight ammunition cast from plastic, to reduce weight.

Mid-term. Mid-term projects were:

• Sea Link Advanced Analysis is a maritime domain awareness related software project to analyse shipping passing through an area, such as the Indian Ocean, and differentiates innocent commercial shipping from hostile warships.

• Virtual Augmented Mixed Reality for Aircraft Maintenance (VAMRAM) is a teaching aid for technicians learning how to maintain a combat aircraft.

Long Term. Long term projects were

• Terrain Shaping Obstacles involves slowing enemy manoeuvre forces by increasing the lethality of traditional obstacles like mines and barbed wire.

• Counter UAS Rocket Artillery and Mortar or CU-RAM involves developing highly accurate weapons systems to physically neutralise enemy drones or drone swarms.

In announcing the co-development of “air-launched, small, unmanned airborne systems (UAS)”, the choice of products and technologies shows a new approach to DTTI and recognises that the Indian partner must bring credible technological capability to the table.

Similarly, it was decided to co-develop a “Virtual Augmented Mixed Reality” platform for teaching aircraft maintenance because several Indian start-ups have already developed VAR technology.

Aircraft Carrier Technology

Lord explained there is far more US-India cooperation than the seven projects specified in the Joint Statement of Intent. “Aircraft carrier technology cooperation (ACTC) is one of the key areas that we are looking at. It is not on the Statement of Intent, but all projects are not mentioned there”, she said.

ACTC is less about incorporating US systems and platforms into India’s next indigenous aircraft carrier, and more about learning from the world’s premier aircraft carrier operator – the US Navy.

Lessons From Earlier DTTI Projects

With the exception of aircraft carrier cooperation, a key reason for failure of earlier DTTI projects was that, in entering co-development projects, New Delhi and Washington had divergent motivations, with neither side focused on co-developing usable products.

The jet engine technology project, for which both sides constituted a joint working group (JWG) in 2015, had been suspended because both sides could not come to an understanding of what exportable technology would be useful to the Indians. And the US side ran into a challenge in terms of the US export control.

Moreover, US entities were masters of aero engine technologies, while Indian scientists and technologists were struggling to develop the Kaveri jet engine. The Defence R&D Organisation (DRDO) wanted US solutions for unsolved technology challenges, such as high temperature alloys and single crystal blades for the “hot end” of the Kaveri.

US engine makers like Pratt & Whitney or General Electric, would never be prepared to part with intellectual property (IP) and hot-end technology that had cost billions to develop over decades. Nor would Washington grant export control licences for critical engine technology.

Americans would possible leverage manufacturing blueprints for building engines in India as part of their fighter bids in on-going procurements for the Indian Air Force and Navy. That would provide a controversial back door into India’s aircraft procurement.

Comments

The enabling agreements – GSOMIA, LEMOA, COMCASA and BECA have been signed. Signing of GSOMIA and up-gradation of India to the STA-Tier-1 status for trade by the US provides a framework for exchange and protection of classified military information between the U.S industry and the public and private Indian defence companies. Enhanced bilateral exercises, which over the years have increased in scope and complexity have enabled a better understanding of each other’s capabilities and limitations. All these steps provide greater avenues to identify and execute meaningful projects under DTTI.

A Standard Operating Procedure (SoP) to harmonize the processes for identification, development, and execution of projects under the DTTI has been formulated and was ratified last year. The inclusion of Indian private industries and fostering the power of innovators has been a major step in the right direction. Formation and eventual rationalisation of Joint Working Groups (JWGs) has happened over the past few years. JWGs, which are now service-specific, has identified around eight to ten projects each, which will be executed under the umbrella of DTTI. A process of dovetailing the products developed through DTTI in the India defence procurement process has also been formalised by the inclusion of two paragraphs (para 129 regarding co-development and para 130 co-production) in the draft Defence Acquisition Procedure (DAP) 2020.

However, as per the draft DAP, ‘such cases will be progressed under an IGA/specific Project Agreement after clearance from the AoN (Acceptance of Necessity) according to authority based on the ultimate estimated cost of the project.’