Bhutan Prime Minister Lotay Tshering has caused deep concern with his recent interview with a Belgian daily, in which he gave China equal weightage among Delhi, Thimphu, and Beijing in settling the Doklam border dispute.

“It is not up to Bhutan alone to solve the problem,” Tshering told Le Libre, referring to the Doklam plateau where there was a face-off between Chinese and Indian troops in 2017 that lasted more than two months until Beijing agreed to withdraw personnel from the eyeball-to-eyeball situation.

“There are three of us. There is no big or small country, there are three equal countries, each counting for a third,” Tshering added.

His remarks give the impression that the Bhutanese government, as well as its able monarch, are fast arriving at the conclusion that they must resolve their disputed boundary with the huge economic power sooner than later.

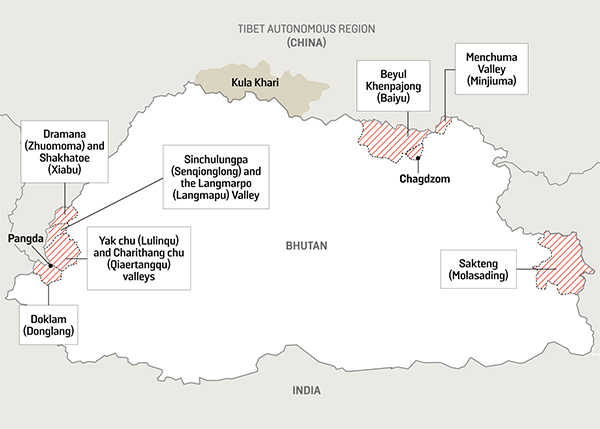

The situation is exacerbated by the fact that in June 2020, China laid claim to the Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary in eastern Bhutan. China has also built several villages, allegedly inside Bhutanese territory, but Tshering dismissed the claims in the interview.

The Bhutanese PM’s remarks come in the run-up to the third anniversary of the stand-off between India and China in eastern Ladakh. All this time, 17 rounds of talks have taken place to maintain stability in the area after the unfortunate incident in the Galwan Valley, in which both Indian and Chinese soldiers lost their lives.

Keeping a close watch

For India, Tshering’s remarks are significant. If Tshering is now saying that China has an equal right in the resolution of the Doklam dispute, then it is sure to change perceptions all around.

Remember that in the summer of 2017, Indian troops moved into the Doklam plateau to prevent the Chinese from extending a road it was constructing toward an adjoining hill feature called the Jhampheri ridge. If the Chinese had been able to build their road, they would have been within kissing distance of Chicken’s Neck — the Siliguri Corridor — that connects the Northeast and the Indian mainland.

With the situation in eastern Ladakh having flared up in the last two years, certainly, the Bhutanese next door are closely watching. Even they would have realised that it is not easy for India to deal with China’s rising power and that Beijing, especially after Xi Jinping’s recent consolidation as the supreme leader, is not ready to give an inch to its pesky neighbours.

In fact, with Russia ready to become an able partner in the evolving geopolitical sweepstakes against the United States — the Ukraine conflict being the touchstone — China probably feels that this is the right time to ram through a resolution of its remaining two border disputes. China shares its borders with 14 countries.

Surely, the Bhutanese would have thought that if Delhi, which is a serious rival to China, still hasn’t been able to resolve its dispute with Beijing, what chance did Thimphu have?

Reviving the 1992 agreement?

In the interview with the Belgian daily, Tshering also gave an interesting deadline for the resolution of the dispute with Beijing.

“We are not experiencing major border problems with China, but some territories have not yet been demarcated. After one or two more meetings, we will probably be able to draw a dividing line,” he said.

It seems that the Bhutanese government is considering a return to the 1992 agreement with Beijing, in which, according to reliable sources, it agreed to resolve the disputed borders in the Doklam region in exchange for territories in the north. It also appears that the northern lands also include some grazing areas that belong to the Bhutanese king.

For the last few decades, the Bhutanese king and his elected government have been able to fend off a resolution, probably keeping in mind Delhi’s sensitivities.

With the India-China dispute remaining unresolved, and, in fact, becoming more implacable — to the extent that the Chinese have actually attempted incursions, especially in eastern Ladakh — Delhi would have advised Thimphu to ‘go slow’ with Beijing, in the hope that it could come to some sort of face-saving agreement with China.

But Tshering’s interview clearly indicates that the Chinese are losing patience with Bhutan. We know that they are pressing for the 25th round of border talks with Thimphu, and that in January this year, the Bhutanese and the Chinese held a meeting in the southern Chinese city of Kunming where they discussed a “three-step roadmap” to settle the border dispute.

We also know that the very close relationship between India and Bhutan implies that the latter is keeping Delhi fully briefed on the evolving talks between Beijing and Thimphu.

Lotay Tshering’s public remarks have cast a ripple in the still waters. Certainly, they will have an impact on how India looks at its northern neighbourhood.