Part 1 – India-China Relations and Territorial Disputes

READ ALSO: Can There Be Rapprochment Between India and China—Part 2)

Events of the last three years in and around China, in the Indo-Pacific, in Europe and Russia have been fast paced.

The Chinese have become increasingly assertive in recent years, especially since Xi Jinping consolidated his position. Even before the pandemic set in, wolf warrior diplomacy emerged in 2017 characterised by the use of confrontational rhetoric by Chinese diplomats and coercive behavior. It was tied to Xi Jinping’s political ambitions and foreign policy inclinations. There was a backlash and a realignments have begun to take place to keep China in check.

Since the outbreak of the pandemic China has sparred with Malaysia and Vietnam, with Philippines and the US in the South China Sea, threatened Taiwan, revoked Hong Kong’s autonomy, chased Japanese fishing boats, traded barbs with the US and is now challenging India at the Line of Actual Control.

Territorial Fronts

China has opened four territorial fronts in the last decade, deploying coercive tactics 1) in the East China Sea, 2) South China Sea, 3) China-India border, and 4) toward the US on the question of freedom of navigation.

The China-India border was once thought to be among the more stable of these fronts. What is surprising is that China has taken up all these fronts at the same time.

China has increased domination in affairs outside its borders along with modernisation of its armed forces to conduct operations in the western Asian region and to protect its eastern seaboard from US carriers and bombers

China has increased its role in the Indian Ocean by building naval bases and also making incursions using its navy and the naval militia flotilla

China has fortified and militarised islands in the South China Sea as well as the Sea of Japan.

Aggressive Behaviour

China has thrown its weight around across the globe in the last three years, unmindful of whom it offended.

Early in 2020, Chinese officials escalated their “wolf warrior” diplomacy, aggressively and undiplomatically attacked countries and individuals they believed had slighted China.

In April 2020, China retaliated against Australia’s call for an inquiry into the origins and spread of the coronavirus by launching a trade war.

In July 2020, Beijing imposed a new national security law on Hong Kong designed to crush the pro-democracy movement.

China was aggressive as well in its dealings with Taiwan as the Trump administration strengthened its ties with Republic of China.

China also continued its systematic repression of its Uighur minority in Xinjiang.

The Chinese communist state with capitalist characteristics has become a country developed enough to export small and big products and weapons to the developing world. China has become the factory of the world, with its cheap labour.

But by end 2020, China was convinced that it was winning its economic contest with the West and it embraced steps designed to decouple its economy from the West on its own terms.

China is also trying to control a number of small nations through debt trap strategy.

What is China Doing Against India?

On the Indian borders, a deadly bloody clash took place, on 15 June 2020, for the first time in 45 years, during the period of lockdown, in the Galwan Valley of Ladakh, in which 20 Indian soldiers died and an unknown number of PLA soldiers were killed in hand-to-hand combat. No shots were fired. I will return to this later.

Till 2020, China’s aggressive attitude was mainly focused on the South China Sea but now it’s turned in India’s direction.

Besides creeping up into India territories, China is trying to surround India by getting involved in its neighbouring countries.

PLA Navy ships have increased their forays into the Indian Ocean region. Chinese submarines and destroyers have been docking in countries like Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Pakistan.

China is also strengthening airbases in Xinjiang and Tibet, some of which are for both civilian and military use.

India, by contrast, has always played it very cautiously with its powerful neighbour. It’s never made a statement on minorities in Xinjiang, an extremely delicate subject for the Chinese. Similarly, when it comes to Hong Kong, India has not uttered even a murmur.

India obviously has to play it super-carefully with its powerful and super-aggressive neighbour which has an economy that is about five times India’s.

India-China Relations in Brief

India gained independence in 1947 and established diplomatic relations with Taiwan. The Chinese People’s Liberation Army defeated the Kuomintang and took over Mainland China, establishing the PRC on 1 October 1949. India was the first non-communist nation in Asia to establish diplomatic relations and recognize PRC as the legitimate government of both Mainland China and Taiwan on 1 April 1950.

In 1950 China marched into Tibet and, in 1954, India signed an agreement recognising Tibet as part of China. In 1959 the Dalai Lama escaped and sought political asylum in India. Today, a Tibetan govt-in-exile functions from India. China is extremely sensitive about the Dalai Lama’s political activities.

Border disputes resulted in a short but traumatic war for India on 20 Oct 1962. In the north, China occupied Aksai Chin in 1957 and has not vacated it since then. Instead it made an all-weather highway through it to Xinjiag. In the East, it reached the plains of Assam before declaring a unilateral ceasefire on 21 Nov 1962 and withdrawing.

India has strengthened its defences and infrastructure on the Chinese border and also modernised its armed forces. So have the Chinese. There have been agreements to open the Nathula Pass in the East for symbolic local trade and a route for annual pilgrimage by Indians to Mount Kailash in Tibet.

During bilateral visits, agreements for maintaining peace on the Line of Actual Control and Confidence Building measures have been signed.

There have been some significant border stand-offs

* The 2013 Depsang standoff lasted for three weeks

* In September 2014 People’s Liberation Army entered two kilometres inside the Line of Actual Control in Chumar sector.

* In June 2017 Chinese troops began extending an existing road southward in Doklam, a territory which is claimed by both China as well as India’s ally Bhutan. This posed a security threat to India’s narrow Siliguri corridor. The stand-off ended in August 2017, when both sides agreed to disengage in Doklam.

* On 10 May 2020, Chinese and Indian troops clashed in Nathu La in Sikkim, leaving 11 soldiers injured.

India’s China Policy

As I said earlier, When India recognised the PRC on 1 April 1950, it broke off relations with Taiwan and also recognised Tibet as a part of China. Adhering to its One China policy was understandable provided India-China relations were stable. Delhi is aware that, any deviation or even a hint of deviation from this policy has an immense psychological impact on China, especially since India hosts the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government in exile.

The Dalai Lama has a huge following amongst Tibetans the world over. He is a demi-God. One word from the Dalai Lama can cause riots and self immolations in Tibet.

Since the Ladakh standoff, India has stopped using the term One China policy. India has also become more open in supporting the Dalai Lama thus challenging China’s core beliefs.

Disputes with India

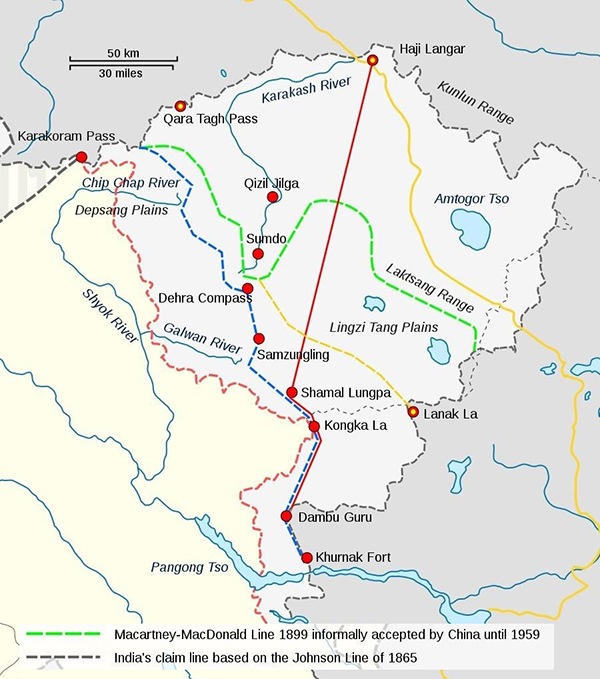

For ease of understanding, the India-China border can be divided into three areas – western sector, middle sector, and eastern sector as shown on this map.

Western Sector

This sector comprises the area between Ladakh to Tibet and the Kunlun mountain range and also extends from Wakhan (Afghanistan edge) to the Karakoram Pass, thereafter following the alignment of the Kunlun mountain range.

The border length of the western sector is 1,597 kms. India’s claim is based on the Treaty of 1842 which was signed between the representative of Maharaja Gulab Singh, former ruler of J&K, with Lama Gurusahib of Lhasa and the representative of the Chinese emperor.

It needs to be understood that China was ruled by the Qing dynasty till 1911 before it was replaced by Chinese nationalists led government, called the Republic of China or ROC in 1912. In 1949, power shifted to the People’s Republic of China or PRC.

At various times in history the British drew lines on the map to depict the border in Aksai Chin as they saw fit. The Johnson Line is shown in grey dashes on the outer edge of Aksai Chin. The McCartney Line is shown in Green. The final line was the Johnson Line of 1912, which India followed after it got Independence and it when it published the map of the area in 1954.

By all standards, this area is the most challenging task for the border negotiations. The China-Pakistan collusivity, Karakoram highway, CPEC corridor and the renewed infrastructure development with increased settlement of the civil population has further reduced the flexibility of negotiations. China Land Border Law, which came into effect on January 1, 2022, has already changed the tenets of territorial disputes to sovereignty disputes.

Middle Sector

This comprises the states of Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand. This is the least disputed sector and covers 545 km of Indian borders. Except for one large claim in the Barahoti sector in Uttarakhand, other claims and counterclaims are minuscule.

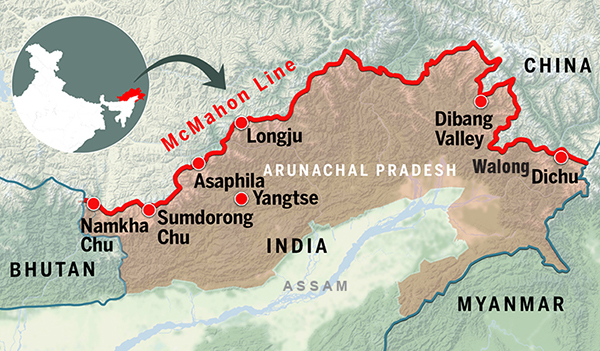

Eastern Sector

The eastern sector conventionally refers to Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh, but both these states have Bhutan separating them. Though Sikkim has a land border of only 220 km and has been witness to both the 1962 as well as 1967 Nathula-Chola conflicts, the situation has normalised a lot after it joined the Indian state on May 16, 1975.

China finally recognised Sikkim as part of India in 2003 in a reciprocal statement by India to re-emphasise Tibet being part of China. An understanding with Bhutan will also be essential for the resolution.

Direct discourse between the British and Tibetans continued till 1908. In 1911, in the last year of the Qing dynasty, Tibetans revolted and asked for British intervention.

A tripartite conference was held at Shimla between the representatives of British India (McMohan), Tibet and China. Deliberation commenced in November 1913 and the McMohan Line was drawn and initialed by all the three representatives in the draft document on April 27, 1914. This document was not formally signed by Chinese representatives in the main document.

The land border, as per this line, covers a length of 1,126 km. This document was finally signed by Britain and Tibet on July 3, 1914.

The border in Arunachal Pradesh, as per the McMohan Line, has been a part of China’s formal offer for border settlement but not by itself. It has been proposed only in lieu of seeking a concession in the Aksai Chin area in Ladakh. The LAC also has a large number of areas of differing perceptions which remain a cause of regular skirmishes or local conflicts.

There have been Efforts to Resolve Disputes

A Special Representatives mechanism was institutionalised between India and China for talks on the boundary question. The 22nd edition of talks was held in New Delhi in December 2019. The SR talks have developed a three-part role — the original mandate of searching for a political settlement to the boundary question, management of borders, and a forum for strategic dialogue.

One important achievement to their credit is the the agreement of 2005 on political parameters and guiding principles for the boundary settlement.

On the substanbtial issue of the boundary disputes there has been no traction. There is not even an agreement of which maps to use while discussing the each other’s positions.

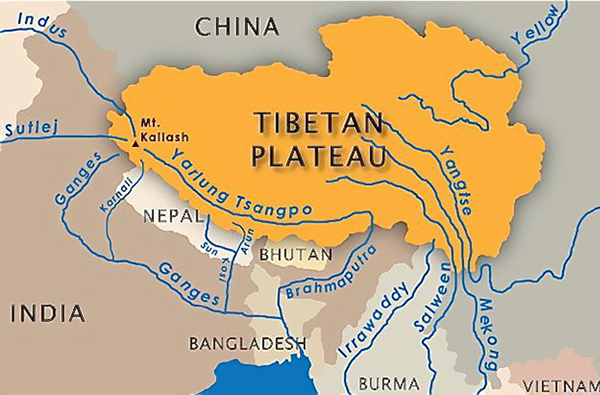

Water Sharing Disputes

Besides territorial disputes, India and China have water sharing disputes.

A total of seven rivers that start in Tibet flow through India.

India’s formal recognition of Chinese sovereignty over Tibet constitutes the single biggest security blunder with lasting consequences for Indian territorial and river-water interests.

India has concern with China’s water–diversion, dam–building and inter–river plans. Moreso, in a conflict, India fears that China can use the rivers as leverage. China has already constructed ten dams on the Bhramaputra and its tributaries and there has been talk of China building a mega–dam at the “great bend before the Brahmaputra river enters India.

China does not cooperate with regard to timely sharing of information related to projects which would impact water sharing; nor does China allow Indian experts to visit dam sites.

READ ALSO: Can There Be Rapprochment Between India and China—Part 2)