Rivalry in the IOR and Future Prospects

Rivalry in the Indian Ocean

READ ALSO: Can There Be Rapprochment Between India and China—Part 2)

The map alongside shows the major sea routes between East and West and the choke points on the Sea Lanes of Communications. India, with its unique peninsular shape jutting into the Indian Ocean makes it the biggest player in the Indian Ocean Region.

The Indian Ocean Region stands out for its economic potential and riches, as follows:

• 28 states (21 are members of the IOR Assn)

• 17.5% of global land area

• 35.0% of the world’s total population (2.6 bn of which 1.3 bn Indian)

• 16.8% of all oil reserves

• 27.9% of all natural gas reserves

• 35.5% of global iron production

• 17.8% of world gold production

• 28% of global fish capture

• Major sea routes connecting East and West

• 50% of world’s sea-borne oil

• 23 of the world’s top 100 container ports

China seems to be on its way to building a global alliance system of its own. China aspires to equal and eventually surpass America.

It is well known that China has increased strategic engagement and military exchanges with Russia, Pakistan, and Iran.

Next are South-east Asian nations including Myanmar, Cambodia, Thailand, and Laos as well as states further afield such as Egypt and Brazil.

However, China has a formal mutual defence treaty only with North Korea. Pakistan is like a client state. Compared to China, US alliances involve mutual defence clauses, extensive troop-basing agreements, and joint military capabilities.

Many friendly countries also fear China’s rise. There is a trust deficit. Except Russia, most have deepened ties with China primarily for economic reasons including New Zealand.

From Brown to Blue Waters

The establishment of a naval logistics facility in Djibouti in 2017 was justified by the Chinese government claiming that it will support peacekeeping operations, the protection of overseas citizens, anti-piracy operations, and protection of regional BRI-related investments.

The PLAN commissioned its first aircraft carrier, the Liaoning, in 2012, its second and third aircraft carriers are afloat. Since then it has deployed Type 55 guided-missile cruisers, Type 52C/D destroyers and Type 54A frigates for anti-piracy operations.

It is also expanding its fleet of replenishment and auxiliary vessels, including oilers, salvage and rescue ships, hospital ships, and transport vessels.

China has increased its military-related engagements with countries in the IOR. Its aggregate number of outbound naval port calls and international military exercises began rising dramatically in 2013.

Both conventional and nuclear-powered submarines have undertaken patrols in the Indian Ocean and made port calls at friendly countries.’

Chinese Navy Buildup

The Chinese have other priorities such as Taiwan and Japan before they can come to Indian Ocean. And if they try to deploy a carrier, India is capable enough to handle them.

Nevertheless, China has been constructing aircraft carriers at a fast pace with a projected plan to operate 10 carriers by 2050. At present their third and most advanced aircraft carrier is being built with the first one, Liaoning, being commissioned in 2012 and second, Shandong, in 2019.

Similarly, Currently, PLANSF operates a fleet of 66 submarines which include nuclear as well as conventional submarines. 7 Ballistic missiles submarines are in service (8 more are planned).

Future Prospects

So, Can China and India come to an understanding on the territorial disputes between them?

Will India and China accommodate each other’s spheres of interest and spheres of influence?

Finally, Can India and China get along in the future?

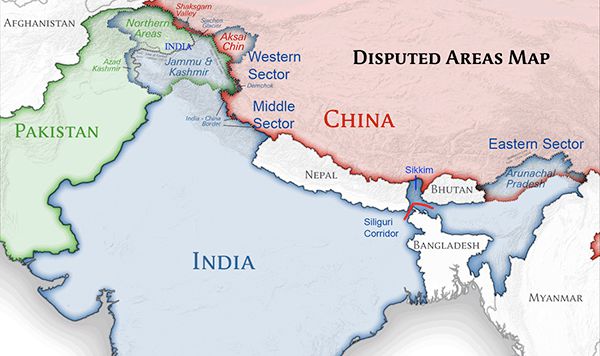

When it comes to territorial claims, the problem with China is that it conjures up the boundaries of the Qing Dynasty to show all of Tibet, parts of J&K and Arunachal Pradesh. But that is the Chinese version of history and Chinese maps.

However, findings of a project report presented on 23 Jun 2022 at the US Congressional-Executive Commission on China conclude that Tibet was never a part of China before the People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded it in 1950. Maps from the Ming and Qing dynasties were presented to prove that Tibet was never part of a Chinese empire.

On the question of territorial disputes, the first requirement is to restore the status quo ante on April 2020. India has been consistently maintaining that peace and tranquillity along the LAC were key for the overall development of the bilateral ties.

India and China have held 15 rounds of military talks so far to resolve the eastern Ladakh row. As a result of the talks, the two sides completed the disengagement process last year on the north and south banks of the Pangong lake and in the Gogra area.

In September 2022, before the SCO summit in Samarkand on 16 September 2022, both sides agreed to further disengagement.

Each side currently has around 50,000 to 60,000 troops along the LAC in the sensitive sector.

China seems to be exploring a new India strategy that rests on exhibiting its strength advantage (by normalizing border conflicts like the Galwan Valley clash) alongside tactical cooperation (by ensuring that there isn’t a complete breakdown in bilateral ties and keeping the door open for working together when it is in Chinese interest).

At the same time, escalation of tensions or a full-scale conflict is carefully averted so that the United States, whom China considers its principal adversary, does not get to reap a benefit from the situation.

It must be noted that since 1962, the Indian Army is deployed on the Chinese borders vary of any land grab by the Chinese as happened in Sumdorong in 1986. Despite 22 rounds of talks between the SRs no progress worth its name has been made in resolving the territorial disputes.

In the Western Sector, ie, Aksai Chin, the Chinese have made the Sinkiang highway and have planned another one. All creeping forward actions in Ladakh are to protect the new highway from Indian threats. They are unlikely to give up their claims in this area at all.

China is in possession of the Shaksgam Valley ceded illegally by Pakistan to China in 1963. This was also done at China’s request to give depth and for the security of the Karakoram highway.

In fact, the Chinese would like to destroy the road infrastructure and the landing strips made close to the LAC in Ladakh to deny it to Indian forces.

In Southern Ladakh, the Pangong Tso area provides avenues for the Chinese advance to Leh. For tactical reasons, the Chinese will never agree to give up their claims in that area.

In the Eastern Sector, China claims the whole of Arunachal province as Southern Tibet. They have never recognised the McMahon Line as the border between India and Tibet. But indications have been given that they could be amenable to a trade off based on settled populations. It remains to be seen what they mean by settled populations since when residents of Arunachal apply for visas to visit China they issue them on separate paper slips and not on their Indian passports claiming that residents of Arunachal are citizens of China.

Expanding the scope of China’s interests further, Beijing’s Western Development Strategy, its BRI or Two Oceans Strategy, that is, China’s own version of Indo-Pacific, aimed at connecting the Pacific and Indian Ocean economies under Chinese leadership and opening up a dedicated Indian Ocean exit for China, rests heavily on India.

India’s cooperation can secure Chinese gains of vital geopolitical and economic consequences, and its non-cooperation can pose the biggest hurdle to China’s South Asia strategy and advancement of its Indian Ocean footprints.

But to solicit this Indian cooperation, China is unwilling to pay a strategic cost or make any real tradeoff, such as accommodating India’s concerns or aspirations on the disputed border or South Asia or concerning its membership of international organizations.

Deep down, China recognizes India as a key threat that can intercept its energy lifelines, has the potential to replace it in global supply chains, and can compete with China in various international bodies, thereby challenging China’s ability to achieve an “overwhelming power advantage in Asia.”

China may well ask, “What if India manages to get these concessions from China, but still chooses to cooperate with the United States?”

India’s membership of the QUAD, with its political, military, and economic implications also makes China vary of India.

India will never approve of China’s BRI initiative since it has become clear that the real purpose is to help China gain access to strategic infrastructure and potential bases in India’s neighbourhood.

India’s Options

India would do well to come to terms with and perhaps leverage its increasing strategic value to China.

By taking a leaf out of China’s own playbook and consistently emphasizing India’s fundamental and growing importance in influencing Chinese strategic outcomes Indian policymakers can potentially extract greater concessions and conciliation.

The Tibetan govt-in-exile, the Dalai Lama’s succession, Taiwan, QUAD, BRI, its naval power projection in the South China Sea, its leadership role in global organisations, US-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) (aimed at countering China’s Belt and Road Initiative in low and middle-income countries), India’s own growing bilateral relations and relevance with Japan, Australia, Vietnam, Iran, SAARC countries and the clout offered by a growing economy and market size are levers that India can use against China.

India must also consider the following steps to dissuade China from precipitating problems for India: –

• Improvement in geopolitical, cultural. and military relationships with BIMSTEC and other Countries in IOR.

• Make tangible investments in the countries in IOR, for strengthening their infrastructure and meet their military needs, to mitigate their overdependence on China.

• Appreciate the importance of India’s relationship with Russia and initiate measures to reassure Russia to fortify that relationship.

• Upgrade capabilities of its defence forces and Coastguard on priority.

Conclusion

My conclusion is that:

The on-going Sino-Indian border crisis has revealed that China has little respect for India’s long-standing efforts to freeze the status quo along the two countries’ disputed frontiers or for New Delhi’s cautious efforts to avoid the appearance of balancing against Beijing.

Rather, it has chosen to expand its control over new parts of the Himalayan borderlands through brazen actions that confront India with the difficult choice of either lumping its losses or escalating through force, if the negotiations presently under way yield meagre returns.

It has forced India to join the rest of Asia in figuring out how to deal with the newest turn in China’s salami-slicing tactics, which now distinctively mark its trajectory as a rising power.

Over the centuries China looked up to Buddhist India. A millennium later, India held Imperial China in great regard. Today, China does not see India as a fellow great power. From a position of strength China does not see the need to accommodate India.

The opposite applies to India. From a position of weakness India feels it cannot afford to accommodate China without loss of standing and strategic autonomy.

Compared to the enormous disparities in economic strength, India and China are not as far apart in military strength. Given the stopping power of the Himalaya and the maritime distances, the imbalance is less daunting.

There will be more Ladakhs. China is likely to be more aggressive on Arunachal Pradesh, which is strategically more important because it’s rich in resources.

China’s comprehensive national power is about seven times that of India. Until India substantially closes the power gap, there’s little prospect of a lasting rapprochement.

READ ALSO: Can There Be Rapprochment Between India and China—Part 2)