The People’s Liberation Army was formed as an armed wing to counter the Anti-Communist purges during the civil wars. Initially called the Red Army, it grew under Mao Zedong and Zhu De from 5,000 troops in 1929 to 200,000 in 1933. Now it has 2.03 million active and 510,000 reserve personnel.

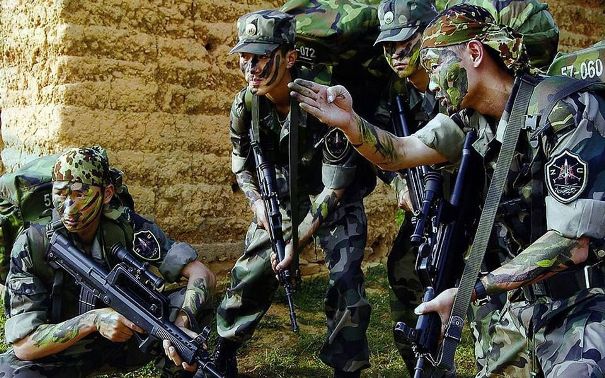

China’s vision of having a world-class army by 2049 has been widely discussed and publicized. However, military experts have questioned this vision owing to several distinct weaknesses plaguing the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

Chinese PLA is currently the world’s largest active military force. It traces its roots to the 1927 Nanchang Uprising of the communists against the Nationalists.

The People’s Liberation Army was formed as an armed wing to counter the Anti-Communist purges during the civil wars. Initially called the Red Army, it grew under Mao Zedong and Zhu De from 5,000 troops in 1929 to 200,000 in 1933. Now it has 2.03 million active and 510,000 reserve personnel.

S. Desai, a research analyst for the China Studies Programme explains that PLA had two important turning points. First, the US’ use of advanced and sophisticated weaponry in the first Gulf War of the 1990s compelled PLA to pursue technological advancement.

Second, he says that the Central Military Commission (CMC) chairman, Xi Jinping’s championing of the Chinese dream to make PLA a world-class force by 2049 led to its restructuring and rapid modernisation.

However, Desai argues that despite the technological advances and growing military might, PLA has several key weaknesses. “One, PLA is accused of being infected by the peace disease (Hépíng bìng), peacetime habits (Hépíng jixí) and peace problems (Hépíng jibì), as it has not participated in any war since 1979.

This is a condition where a soldier’s casual peacetime approach while training could impact wartime combat readiness,” he writes.

He further says that Xi Jinping knows about this weakness and has therefore introduced changes to PLA’s regime to make it train under “realistic combat conditions”.

“My research also indicates that the number of PLA’s bilateral-trilateral military exercises with the foreign armies has increased since 2014 to compensate for the lack of combat experience. But the impact of this change cannot be verified until PRC goes to war,” says the author.

The second weakness that Desai talks about is that PLA’s military modernisation doesn’t make up for the quality of personnel employed, especially in the technology-centric services such as the navy, air force, rocket force and the strategic support force.

China has one of the largest defence budgets and has allocated the most significant share of spending on capital expenditure. To overcome this, PLA improved its recruitment technique by focusing on employing better-qualified students from specialised and technical universities.

“It felt the need to rework its conscription model to achieve the informatisation goal for the armed forces by 2035, which was announced by Xi in the 2017 party congress,” says Desai. He added that it introduced several financial incentives to attract highly educated talent. However, despite positive inducements, recent reports suggest that the gap still exists and PLA is still facing a shortage of skilled expertise to drive its technology-centric services.

After widespread corruption in the PLA in the 1980s, the then chairman, Jiang Zemin introduced reforms that tried to address this problem by dissolving the military-business complex in 1998, but by then the problem had become pervasive.

After Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, he launched more than 4000 anti-graft investigations that resulted in the sacking of high-level officers. To compensate for the loss of position of influential officials which could’ve led to resistance within the army, they were given appropriate positions throughout the rank and files of PLA.

“Although this has reduced the resistance, the effectiveness of the reforms, which were meant to reduce corruption, can be questioned,” says Desai.

Another weakness the Desai brings forward is the rising revenue expenditure of the PLA. “China also has the largest pool of 57 million PLA veterans, demanding post-retirement benefits and better retirement deals. These post-retirement wages, pensions and living subsidies are incurred from China’s defence spending. Rising revenue bills, since 2018, will certainly impact capital expenditure in the near future,” he states.

Another revenue expenditure is the commissioning cost to maintain existing weaponry. Thus, the author concludes that the rising revenue bills and increasing maintenance cost will slow China’s military modernisation drive.

He pointed out that other than these reasons, PLA has other weaknesses such as “limited strategic airlift and open-sea refuelling capabilities, limited overseas military bases, lack of joint operations capabilities and the lack of a rotational system within the lower-ranked officers of PLA”.

He concluded by saying that these limitations will not only impact the Chinese dream but also alter its capabilities to attain its strategic military guidelines in the future.