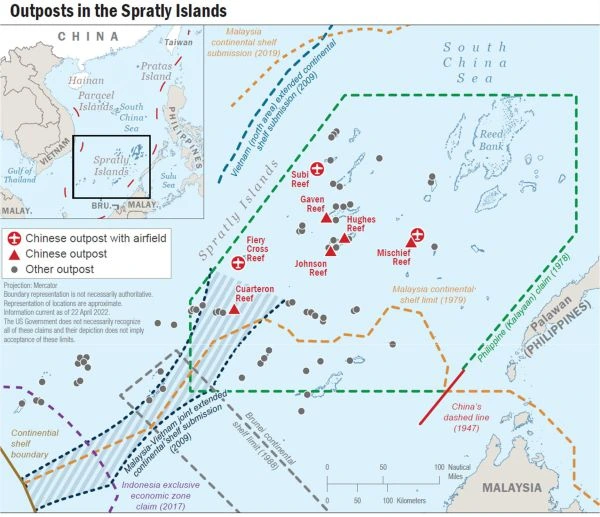

The PRC’s Spratly outposts are capable of supporting military operations, include advanced weapon systems, and have supported non-combat aircraft; however, no large-scale presence of combat aircraft has been yet observed there.

In 2021, the PRC continued to deploy PLAN, CCG, and civilian vessels in response to Vietnamese and Malaysian drilling operations within the PRC’s claimed “nine- dash-line” and Philippines’ construction at Thitu Island.

Security Situation in the South China Sea

In July 2016, pursuant to provisions in the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), an arbitral tribunal convened at the Philippines’ behest ruled that the PRC’s claims to “historic rights” in the SCS, within the area depicted by the “nine-dash line,” were not compatible with UNCLOS. Since December 2019, four SCS claimants (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam) have explicitly referenced the arbitral ruling in notes verbales to the UN denying the validity of the PRC’s “historic rights” and nine-dash line claims. Beijing, however, categorically rejects the tribunal decision, and the PRC continues to use coercive tactics, including the employment of PLA naval, coast guard, and paramilitary vessels, to enforce its claims and advance its interests. The PRC does so in ways calculated to remain below the threshold of provoking conflict.

The PRC states that international military presence within the SCS is a challenge to its sovereignty. Throughout 2021, the PRC deployed PLAN, CCG, and civilian vessels to maintain a presence in disputed areas, such as near Scarborough Reef and Thitu Island, and in response to oil and gas exploration operations by rival claimants within the PRC’s claimed “nine-dash line.” Separately, the CCG blocked two Philippine supply boats on their way to an atoll in the South China Sea and employed water cannons against them, prompting the United States to warn that an armed attack on Philippine public vessels would invoke U.S. defense commitments.

In April 2020, Beijing announced the creation of two new administrative districts in the SCS covering the Paracels and the Spratly Islands. This action were likely intended to further solidify PRC claims in these areas-especially in terms of domestic law- and justify its actions in the region.

In July 2019, China and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) members completed the first reading of the China-ASEAN Code of Conduct (CoC), with a second and third reading remaining before China and ASEAN members finalize the agreement. China and ASEAN member states had sought to complete CoC negotiations by 2021; however, the COVID-19 pandemic has delayed its progress.

When negotiations resumed in November of 2021, China was met with hostility from Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte following the aforementioned CCG actions against Philippine vessels. Negotiations did not produce substantive outcomes, likely because China and some SCS claimants were sensitive to language in the CoC that limits their activities. Given the complexity of the disagreement and ASEAN’s consensus-based process, it is extremely unlikely that there will be a CoC signed in 2022.

South China Sea Outposts Capable of Supporting Military Operations

Since early 2018, PRC-occupied Spratly Islands outposts have been equipped with advanced anti-ship and anti-aircraft missile systems and military jamming equipment, marking the most capable land-based weapons systems deployed by any claimant in the disputed South China Sea to date. From early 2018 through 2021, the PRC regularly utilized its Spratly Islands outposts to support naval and coast guard operations in the South China Sea. In mid-2021, the PLA deployed an intelligence-gathering ship and a surveillance aircraft to the Spratly Islands during U.S.-Australia bilateral operations in the region.

The PRC has added more than 3,200 acres of land to the seven features it occupies in the Spratlys. The PRC has stated the main objectives of these projects are mainly to improve marine research, safety of navigation, and the living and working conditions of personnel stationed on the outposts. However, the outposts provide airfields, berthing areas, and resupply facilities that allow the PRC to maintain a more flexible and persistent military and paramilitary presence in the area. This improves the PRC’s ability to detect and challenge activities by rival claimants or third parties and widens the range of response options available to Beijing

East China Sea

The PRC continues to use maritime law enforcement vessels and aircraft to patrol near the Japan-administered Senkaku Islands. In 2021, the PRC passed new legislation regarding the rules of engagement for their Coast Guard vessels, creating a legal justification for more aggressive patrols.

The PRC claims sovereignty over the Japanese-administered Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea (ECS), which Taiwan also claims. Beijing continues to uphold the importance of the four-point consensus signed in 2014, which states Japan and the PRC will acknowledge divergent positions over the ECS but will prevent escalation through dialogue, consultation, and crisis management mechanisms. The United States does not take a position on sovereignty of the Senkaku Islands but recognizes Japan’s administration of the islands and continues to reaffirm that the islands fall within the scope of Article 5 of the U.S.-Japan Mutual Security Treaty. In addition, the United States opposes any unilateral actions that seek to undermine Japan’s administration of the islands.

The PRC uses maritime law enforcement vessels and aircraft to patrol near the islands, not only to demonstrate its sovereignty claims, but also to improve readiness and responsiveness to potential contingencies. In 2021, the PRC continued to conduct regular patrols into the contiguous zone territorial seas of the Senkaku Islands and stepped up efforts to challenge Japan’s control over the islands by increasing the duration and assertiveness of its patrols. In one instance, China Coast Guard (CCG) ships entered Japanese-claimed waters for more than 100 consecutive days. Japan’s government protested in January 2021, calling on China to ensure that new PRC legislation allowing its coast guard to use weapons in its waters complies with international law. In August 2021, seven CCG vessels-including four equipped with deck guns-sailed into disputed waters around the Japan-administered Senkaku islands in the East China Sea. According to the Japanese coast guard, the PRC vessels attempted to approach Japanese fishing vessels, but were prevented from doing so by Japan Coast Guard Vessels. Increased PRC assertiveness caused Japanese Defense Minister Nobuo Kishi to express “extremely serious concerns” in December 2021 and led to the Japanese and PRC defense ministries to begin operating a new hotline between the two countries to manage the risk of escalation.

Based on the Annual Report by Secretary of Defense to U.S. Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China