Nepal has provoked India by turning a territorial issue into a bigger case of Nepali nationalism and painting India as a hegemon. Nepali prime minister KP Sharma Oli’s exploitation of a dispute over territory was seen as an effort by him to consolidate himself in the Nepal Communist Party government by whipping up ultra-nationalistic sentiments against India.

A new map of Nepal based on an older British survey reflecting Kali river originating from Limpiyadhura in the north-west of Garbyang was adopted by Nepal’s parliament and notified on 20 May. The new alignment adds 335 sq km to Nepali territory, territory that has never been reflected in a Nepali map for nearly 170 years. On 22 May, a constitutional amendment proposal was tabled to include it in a relevant Schedule.

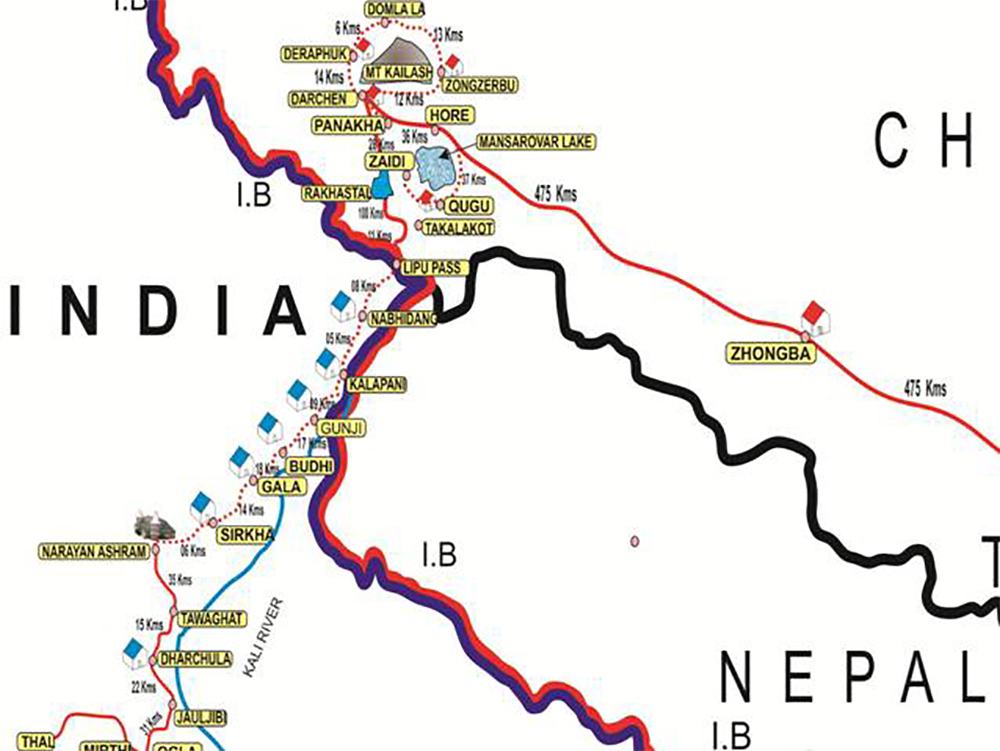

The map, released within a day of the cabinet approval, showed Lipulekh, Kalapani and Limpiyadhura as part of Byas rural municipality in Nepal’s Sudurpaschim province.

In his address to the Nepalese Parliament on May 19, a day before the new map was made public, Oli said, “Those who are coming from India through illegal channels are spreading the virus in the country and some local representatives and party leaders are responsible for bringing in people from India without proper testing”. And then, in a deliberate act of provocation, he made the astounding statement that the “Indian virus looks more lethal than Chinese and Italian now”.

Mansarovar Route

Tension had escalated after India inaugurated a road link connecting Kailash Mansarovar, a holy pilgrimage site situated at Tibet, China, that passes through LipuLekh. The 80 km new road inaugurated by defence minister Rajnath Singh on 8 May was expected to help pilgrims visiting Kailash-Mansarovar as it was around 90 kms from the Lipulekh pass.

A subsequent comment by the Chief of the Army Staff (COAS), Gen ManojNaravane, on 15 May, that “Nepal may have raised the issue at the behest of someone else” riled Oli so much that he asked Nepal’s Chief of Army Gen Purna Chandra Thapa to deliver a public rebuttal to Gen Naravane. But Gen Thapa is learnt to have declined, pointing out that it was a political issue and had nothing to do with the military. It is only after Gen Thapa declined to be dragged into the government’s politics that the Nepal defence minister IshworPokhrel issued a statement criticising Gen Naravane. Like the Indian Army Chief Naranave who is an honorary General of the Nepal Army, Nepal’s Army Chief Thapa is the honorary General of the Indian Army.

Nepal’s Internal Politics

Oli’s move to release a new political map and escalate tensions with New Delhi was designed to consolidate his loosening grip on the party and government.

Under the Nepali Constitution, a new Prime Minister enjoys a guaranteed two-year period during which a no-confidence motion is not permitted. This ended in February unleashing simmering resentment against Oli’s governance style and performance. His inept handling of the Covid-19 pandemic added to the growing disenchantment. Within the Nepal Communist Party (NCP) there was a move to impose a ‘one man, one post’ rule that would force Oli to choose between being NCP co-chair or prime minister.

Oli had won the election in 2017 by flaunting his Nepali nationalism card, the flip side of which is anti-Indianism. This is not a new phenomenon but has become more pronounced in recent years.

By April 2020, Oli’s domestic political situation was weakening. Oli has faced a challenge from senior party leaders and former prime ministers, Pushpa Kamal Dahal “Prachanda” and Madhav Kumar Nepal due to an internal rift within the NCP. The crisis was defused after China mediated a deal between the leaders. If there were any doubts about the Chinese investment in the NCP and backing for Oli, it was dispelled.

The rift and Oli’s own nationalist politics, which seem to disappear when it comes to China, and domestic political opinion resulted in Kathmandu taking a strong position on the question of territory.

Oli appeared to have been driven by two objectives. One was to consolidate himself in the NCP government. Oli has been trying to outdo the two former prime ministers and it was only after the intervention of Beijing that the three power centres in Nepal’s ruling party agreed to stick together.

Two, the new political map puts the focus back on the differences over India’s boundary over the tri-junction point in Nepal’s northwest that separates China and the Tibet Autonomous Region to the north and India’s Kumaon to the south. This effort to put the spotlight also gives China a handle, particularly since it had endorsed India’s position on these territories in 1954 and 2015.

Fissures are clearly visible in the NCP and the government in Kathmandu. The ruling party has 174 seats in the 275-member parliament (121 of CPN-UML and 53 of the Maoist Centre). There is intense faction-fight among these parties and the Maoists have threatened to withdraw support if their demands are not met with.

The map issue has also not gone down well within the party with Oli’s bête noire Bamdev Gautam, vice chairman of the NCP, issuing a statement warning the prime minister not to take credit for the new map. Sooner or later, the parties supporting the government may press their demand for a change in leadership and bring down the Oli government in order to form a new government under a new leader.

Modi’s ‘Neighbourhood First’

Prime minister Narendra Modi has often spoken of the “neighbourhood first” policy. He started with a highly successful visit to Nepal in August 2014. But the relationship took a nosedive in 2015 when India first got blamed for interfering in the Constitution-drafting in Nepal and then for an “unofficial blockade” that generated widespread resentment against the country. It reinforced the notion that Nepali nationalism and anti-Indianism were two sides of the same coin that Oli exploited successfully.

In 2014, when Modi visited Nepal, many South Asia watchers anticipated rekindling of a lacklustre bilateral relationship that did not seem to have found its rightful place in New Delhi’s strategic priorities. Modi’s visit, then for the first time in 17 years by an Indian prime minister, concluded on an upbeat note with promises of ‘H-I-T — Highways, Infoways and Transways’ as the primary areas of cooperation with the Himalayan nation.

Unfortunately, within a year ties between the two neighbours were hit by a slew of setbacks, with the economic blockade of 2015 being the biggest blow.

To keep the outreach alive, Modi followed his first visit with two more in the course of which he laid the foundation stone for the 900 MW Arun III project in Sankhuwasabha district of eastern Nepal and the Raxaul (Bihar)-Kathmandu rail link.

This bonhomie too was short-lived when after the demarcation of the new union territories of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh in November 2019, India published a restructured map that represented Kalapani as part of Uttarakhand. This sparked protests from Nepal, which claims Kalapani — sitting at the tri-junction between Indian, Nepalese and Chinese borders — its own.

The unveiling of the Kailash Mansarovar road link that passes through Lipulekh, near Kalapani, further added to the disquiet.

Comments

Oli, who has been facing problems within the ruling NCP, is seen to have responded to ‘public sentiment’ on the opening of the Mansarovar route through LipuLekh with a new political map that depicted Lipulekh and Kalapani as part of Nepalese territory.

New Delhi will have to closely watch the emerging conflict in Nepal’s ruling party and wait for the outcome. The map controversy seems more of Oli’s one-upmanship rather than a serious security threat. But at the same time, New Delhi will have to impress upon Kathmandu the need to go back to the discussion table soon after the crisis of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic is over.

The current row over the Kalapani border dispute is only incidental in a greater design to destabilise New Delhi’s ties with its neighbours.

Nepal’s new map has broken the agreement between the two countries to maintain status quo till negotiations help resolve the border dispute. India had initially said it would resume foreign secretary-level dialogue mechanism after the Covid-19 emergency. After Nepal issued its new map and Oli’s intemperate reference to India in Parliament, New Delhi has urged Kathmandu to create a positive atmosphere for dialogue. After deferment of the Bill, New Delhi says it is open to engaging to solve border row.

India has ignored the changing political narrative in Nepal for far too long. India remained content that its interests were safeguarded by quiet diplomacy even when Nepali leaders publicly adopted anti-Indian postures — an approach adopted decades earlier during the monarchy and then followed by the political parties as a means of demonstrating nationalist credentials. Long ignored by India, it has spawned distortions in Nepali history textbooks and led to long-term negative consequences.

India remains connected culturally wit Nepal — a void that China or any nation outside the region will take a long time to fill. We should intensify people-to-people exchanges especially among the younger citizens. India should stay committed to its support for inclusion of the Madhesis in Nepal’s political framework, which is a just and fair demand affirming India’s commitment towards creating a more inclusive world.

For too long India has invoked a “special relationship”, based on shared culture, language and religion, to anchor its ties with Nepal. Today, this term carries a negative connotation — that of a paternalistic India that is often insensitive and, worse still, a bully.

The urgent need today is to pause the rhetoric on territorial nationalism and lay the groundwork for a quiet dialogue where both sides need to display sensitivity as they explore the terms of a reset of the “special relationship”.

Complexities underlying India-Nepal issues cannot be solved by rhetoric or unilateral map-making exercises. Such brinkmanship only breeds mistrust and erodes the goodwill at the people-to-people level. Political maturity is needed to find creative solutions that can be mutually acceptable.