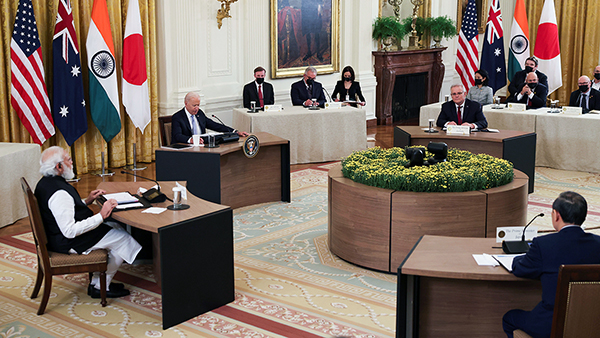

It took people by surprise that a week before leaders of four important countries in the Indo-Pacific got together for their first in-person meeting of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) in the US, three Anglo-Saxon countries announced the formation of AUKUS (a trilateral of Australia, the UK and the US). Questions arose whether the US was dumping the Quad for this new club.

Softer focus for Quad

U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman, during her visit to India and Pakistan, in first week October 2021, clarified the different track compared to security role for AUKUS. At an event in Mumbai, Wendy Sherman claimed that Quad is meant to discuss soft issues, like vaccines, supply chains, and climate. The American “clarification” came after Quad’s four heads of State met in the US in-person, on 24 September, and stressed the rule of law and regional security. It also came just days before Quad’s second phase of the Malabar naval exercise in the Bay of Bengal.

The Quad is a “non-defence, non-military” arrangement, said U.S. Deputy Secretary of State said, indicating at two separate interactions that the purpose of the Australia-India-Japan-United States grouping is meant to cooperate on what are considered ‘softer’ issues.

“The Quad is [a] vehicle which largely operates in security realms that are non-military, non-defence. Things we do together on vaccines, and infrastructure, supply chains, technology and climate — all the forward thinking areas in which we need to gain confidence and ensure security for our people,” Sherman said at an event organised by think-tank Ananta in Mumbai.

In an interview to Pakistan’s official PTV, broadcast, on 9 October, Sherman called the Quad “a cooperative effort to work on things like energy, people-to-people exchanges and infrastructure and supply chain resilience.”

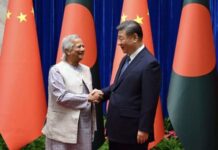

The comments by a senior U.S. official are the clearest signal yet that Washington has shifted its view of the Quad’s agenda, particularly after the announcement of the new Australia-UK-U.S. or AUKUS alliance for nuclear submarines in the Indo-Pacific. The announcement came just a week ahead of the first in-person Quad summit, which Prime Minister Narendra Modi attended in Washington in September.

Indian officials also said the imperatives of the COVID pandemic, including the need for vaccines, technology, supply chain resilience and HADR (Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief) operations appear to have “clarified” the Biden administration’s plans for the Quad.

When asked about the difference between the Quad and AUKUS at the Ananta interaction, Sherman replied that the two were non-competing “pieces of a puzzle”.

“AUKUS is a one of a kind project, which will be a game changer in a maritime sense in this arena,” Sherman said, speaking about the project for the U.S. and UK to help Australia build a fleet of nuclear propelled submarines “which are faster, harder to detect, more agile”.

Former Indian Ambassador to China Gautam Bambawale, says that in his view, the U.S. position has not shifted. “Quad may not be a military alliance, but it continues to undertake military activities like the Malabar Naval exercise.”

Sherman’s words were in stark contrast to those of Michael Pompeo, the former U.S. Secretary of State during the Trump administration, during the Quad’s Ministerial level meeting just a year ago. “As partners in this Quad, it is more critical now than ever that we collaborate to protect our people and partners from the Chinese Communist Party’s exploitation, corruption, and coercion. We’ve seen it in the south, in the East China Sea, the Mekong, the Himalayas, the Taiwan Straits,” Pompeo had said in his opening statement in Tokyo in September 2020, where he lashed out at the Chinese government’s “authoritarian nature” and criticised it for the Covid pandemic.

The Quad is a club into which India was wooed ardently. Yet, it remained circumspect. It is largely because of India that the Quad remains a non-military club of regional democracies with a “shared vision of a free and open Indo-Pacific”. AUKUS, on the other hand, is an unabashed security pact; the announcement of its formation came with the news that the UK and the US would help Australia develop and deploy nuclear-powered submarines. The message of taking on China is unambiguous.

India now has the 2+2 dialogues with all three Quad partners, thus maintaining a defence engagement with each, but out of the ambit of the plurilateral.

At the first India-Australia 2+2 ministerial meet in early September, India’s foreign minister, S Jaishankar made an important clarification regarding the Quad. In response to reports in the media of Chinese attempts to portray the Quad as an “Asian NATO”, Jaishankar said that it was a seeming “misrepresentation of reality”.[1] The Quad, he averred, was but a “platform for four countries to cooperate for their benefit and for the benefit of the world…Unlike NATO, a Cold War term, the Quad looked very much to the future, reflecting globalisation and the compulsions of countries to work together.”

Before the Prime Minister‘s US visit in September 2021, foreign secretary Harsh Vardhan Shringla said Quad was separate from AUKUS, and for that matter, was not lined with the Malabar exercise either, though the same nations were involved in both the Quad and Malabar. It was assumed at that time that India was trying to downplay the role of Quad to assuage any jittery nations in Asia.

That explanation, evidently, did little to convince mandarins in Beijing. Ahead of the Quadrilateral summit in New York in late September 2021 — the first in-person meeting of these country leaders—a Chinese spokesperson denounced the Quad as “a clique formed to target a third country.” The group’s “zero sum thinking and ideological bias”, the official complained, “was unsuited for trust building and cooperation between regional states.”

Australia’s inclusion in the Malabar naval exercises imparts more than a military dimension to the Quadrilateral; it in fact signals unified resolve to Beijing.

At present, the main mechanism for technology cooperation in the Quad is the Critical and Emerging Technology Working Group (or the Quad Working Group) established in March 2021. The Working Group announcement highlighted three broad areas for collaboration: 1) Telecommunications; 2) Principles on technology development, design, and deployment; and 3) Collaboration between national standards bodies. There also exists a Track 2 initiative, supported by Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, called the Quad Tech Network, which promotes research and public dialogue on technology issues, focusing on the Indo-Pacific.

The Quad nations came together in the backdrop of China’s modernisation of its military, intrusions into the Taiwan Strait, and its force projections even though they have refrained from taking China’s name formally either as an opponent or challenger in the Indo-Pacific region. The ambiguity about China being the adversary, thus, continues.