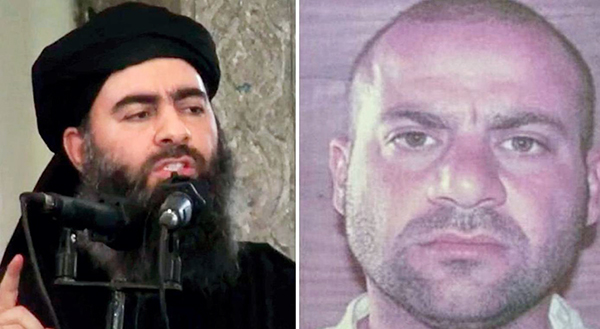

On 21 May 2020, Iraqi intelligence agencies claimed to have arrested Amir Mohammad Rehman al-Salbi alias Abdullah Qardash (Salbi hereafter). This was the man who had succeeded Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi as the new leader of Islamic State in Iraq & Syria (ISIS) in November 2019 following the latter’s death at the hands of US Special Forces in the Barisha Raid the month before. Initial intelligence eventually, however, proved false, the arrested man being identified as Abdul Nasser Qardash (hereafter referred to as Nasser Qardash), an ISIS leader close to Salbi and one of the potential successors to Baghdadi after his death.

The appointment of Salbi as Baghdadi’s official successor and Nasser Qardash’s confession during his interrogation at the hands of the Iraqi authorities, however, reveal numerous details regarding ISIS’ current and future strategy after the loss of its physical caliphate in the Middle East in March 2019. As the world and India reel from coronavirus, post-Baghdadi ISIS has spent its time quietly regrouping and re-strategising its comeback. This will have major security-related and geostrategic consequences for India, especially given the added blow dealt by Cyclone Amphan in Bengal and the looming threat of resurgent Pakistani Inter-Serrvices Intelligence (ISI)-sponsored terrorism in Kashmir – the so-called ‘The Resistance Front’ (TRF) attempting to pick up the pieces of the Pakistan-sponsored jihadist movement in the Valley.

Growing non-Arab and ISIS’ Focus on Kashmir and Bengal

Salbi’s appointment itself came as a surprise, given his ethnic background – which also provides clues regarding the Islamic State’s implied focus on acquiring influence in regions such as India, which lie beyond the Arab world. Despite US President Donald Trump’s tweet in November 2019, claiming that he had received information regarding Baghdadi’s new successor, it was only in January 2020, when Western and regional espionage efforts identified Salbi, an ethnic Turkmen hailing from the town of Tal Afar in northern Iraq as the new leader of ISIS. The appointment of a non-Arab to a position of such stature is as significant as it is unprecedented. Global jihadist organisations, such as ISIS, have often been believed to use radicalised non-Arab Muslims as foot-soldiers, with ethnic Arabs usually holding the most important positions. A 2015 report by Research & Analysis Wing (R&AW) and Intelligence Bureau (IB) pointed out that Chinese, African and South Asian ISIS fighters in the erstwhile ‘caliphate’ faced discrimination by the predominantly Arab ISIS Police Force, or the hisbah. Divisions exist even within the ethnic Arabs in such terrorist organisations, with the CIA predicting in the immediate aftermath of Osama Bin Laden’s death that his successor, Ayman al-Zawahiri as a North African Arab, “would have difficulty maintaining the loyalty of Al-Qaeda’s Gulf Arab followers.”

The appointment of a non-Arab like Salbi, therefore, indicates that ISIS after Baghdadi is willing to take unprecedented and unexpected steps to rebuild. More importantly, however, the appointment of a non-Arab as ISIS’ new leader indicates that the terrorist organization will now renew its focus on non-Arab parts of the Muslim world, which includes India. Thus, the symbolism of Salbi’s appointment as the new emir of the so-called caliphate should not be understated as ISIS attempts to expand its influence beyond the Middle East with a key focus on India. The attack on a Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) patrol party in Anantnag by the Islamic State (IS) in Jammu & Kashmir (ISJK) in April 2020 should, therefore, be read in the above context of the Turkmen Salbi leading ISIS into the 2020.

ISIS’ deepened interest in India, however, predates Salbi’s leadership, with radicalised young Indian Muslims travelling to Iraq and Syria to fight for the erstwhile caliphate as early as 2014/15. ISIS’ establishment of wilayahs in West Bengal, Bangladesh and Kashmir in May 2019 came just two months after the loss of its physical territory in March 2019 and a month after the horrific Easter attacks in Sri Lanka by its affiliate there. Such developments highlight that ISIS will target Indians in its quest to prove that it remains a serious player in the global jihadist arena, especially as it focuses efforts on deepening domestic networks in the country. It is also worth noting that just a day after Trump’s tweet on ISIS’ new leader on 1 November 2019, ISIS’ Bangladesh wilayat pledged allegiance to Salbi – among the first of ISIS’ international wilayats to do so. This is deeply significant, given that the wilayat also includes the Indian state of West Bengal. It further underscores post-Baghdadi ISIS’ increased interest in the Indian subcontinent as an area to expand in and its targeting of West Bengal to make headway into India’s heartland. This strategy may be achieved through alliances with local jihadist groups like Jamaat ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB).

Salbi’s Desperation on India

Yet, the symbolism of Salbi’s appointment obscures his deeper psychological worry regarding his new position – his desperation.

Having succeeded al-Baghdadi, who had led the Islamic State since 2010, Salbi has a large power vacuum to fill. His aforementioned non-Arab ethnicity may also play a role in fuelling his desperation to achieve large-scale, television-worthy attacks to bolster his image as a suitable successor to Baghdadi as he seeks to bring the predominantly Arab leadership of ISIS under his direct control. However, this is easier said than done. 2019 saw ISIS lose its physical caliphate in the Middle East as well as much of the infrastructure required for such large-scale attacks following Baghdadi’s death. Hence, ISIS has attempted to play up lone-wolf attacks after Salbi’s takeover. The London Bridge stabbings in November 2019, perpetrated by a home-grown terrorist with roots in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (PoK) and the Streatham stabbings in South London in February 2020, followed by the attacks on boats belonging to the Maldivian Navy in April 2020 were all incidents for which ISIS claimed responsibility. However, these have all been fairly low-intensity attacks compared to the carnage that ISIS was known for causing in major cities during its heyday, from the 2015 Paris attacks to the 2016 Brussels airport bombing and the 2017 Manchester arena suicide attack. Salbi’saforementioned desperation to prove himself is coupled with his growing interest in the Indian subcontinent as an area of expansion.

A recurring characteristic of most famous terrorist leaders in the modern age has been their ability to carry out large-scale attacks that gain media attention whenever they seek to establish their outfit’s name on the global arena. Prior to 9/11 and just days after he declared his famous 1998 fatwa against the USA, Osama Bin Laden’s Al Qaeda carried out a bomb blast at the US embassies in Nairobi and Dar Es Salaam. Salbi has not done so in the months after his appointment – and given his aforementioned complex regarding his position and the murmurs against him in the Arab ranks of the Islamic State’s leadership – he is looking for an opportunity to establish himself as an appropriate or even greater successor to Baghdadi, on the same level as him and Bin Laden.

The lone-wolf attacks that ISIS has sponsored or carried out also provide inkling regarding ISIS targets in India or Indian national interests. The fact that the London Bridge attacker Usman Khan was of Pakistani-origin and had at one time planned to achieve ‘first-hand’ experience in conducting terror attacks in Kashmir before setting up a madrassa in PoK, helps provide a glimpse of ISIS’ plans to foment terror in post-Article 370 and 35A Kashmir. ISIS’ attack on naval boats in the Maldives is also extremely relevant to Indian national security. The attacks on naval boats are ISIS’ signal to India and China too – both nations are vying for naval influence in the Maldives. Furthermore, given the Maldives’ proximity to Lakshadweep, which ISIS had attempted infiltrating from Sri Lanka in May 2019, it is crucial that South Block consider any ISIS activity in Maldives from a national security perspective.

More recently, ISIS attempted to exploit communal rioting and civil unrest in India to attempt establishing a foothold in the country. In February 2020, ISIS, specifically its sub-unit the Islamic State in the Khorasan Province (ISKP), which operates in Afghanistan and South and Central Asia began circulating cherry-picked images of the Northeast Delhi riots to instigate communal tension in the country and widen its recruitment pool. The next month, in its second issue of Voice of Hind, ISKP attempted to continue fanning the flames of communal tension by calling for lone-wolf attacks on policemen and Indian Army officers using “vehicle attacks, knife and axe attacks, arson and poisoning.” This highlights two issues. One, that ISIS under Salbi has firmly targeted India as its next base of operations. Two, that Salbi’s above mentioned desperation, which had earlier translated into lone-wolf attacks in the UK and the Maldives, will soon manifest in India as a result of this desperation. Delhi Police’s arrest of an ISKP-linked Kashmiri couple who had been instigating the riots in February underscores the fact that ISIS aims to use domestic unrest in India as a tool to grow in strength.

Ramifications of the Central Asian Connection

As an embattled and humiliated US withdraws from the wastes of Afghanistan, it leaves ISIS with an opening to expand its influence in Central Asia. Expansion into Central Asia, which ISIS had already achieved to a certain extent under Baghdadi, was forecast to accelerate under Salbi, who himself is of Central Asian ethnicity (Turkmen). This has major security repercussions for India, since Central Asia is India’s opening into Afghanistan and Pakistan, and provides a key source of fighters for the ISI-backed Afghan Taliban.

The ISKP-sponsored attacks in Tajikistan, in particular, are of concern. Among the first ISIS-sponsored attacks under Salbi’s leadership took place in Tajikistan in November 2019, with an ambush on a Tajik checkpoint on the country’s border with Uzbekistan. The location of the attack holds particular significance. The Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, an ISKP-affiliate, provides ISIS with fighters to use in Afghanistan and Pakistan – the attack was hence a signal to the Uzbek government that Tajikistan was being looked at as a base for ISIS movements targeting the Central Asian heartland in Uzbekistan.

This is particularly worrying from an Indian perspective. Tajikistan is home to Farkhor Air Base, India’s only overseas military base. Given its history of providing anti-Islamist fighters in neighbouring Afghanistan with shelter and medical aid in the 1990s (the Indian Air Force medical facility at Farkhorwas where Ahmad Shah Massoud, the ‘Lion of Panjshir’ and the leader of the anti-Taliban Northern Front breathed his last in 2001) and coupled with ISKP’s above mentioned encouragement of attacks on Indian military installations, the Farkhor Air Base will most probably become a key target of attack by the ISIS in the near future. Hence, our political leadership and the MEA must start formulating steps to protect Indian soldiers and military infrastructure on the base at the moment.