Indian troops in Ladakh delayed the annual summer exercise along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in early March after some soldiers were infected by Covid-19, following which Chinese forces moved forward to key strategic positions and cut off access to areas patrolled by Indian forces in the past.

The joint exercise by the Army and Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP) in Sub Sector North (SSN) is carried out every year and is mirrors a similar Chinese exercise.

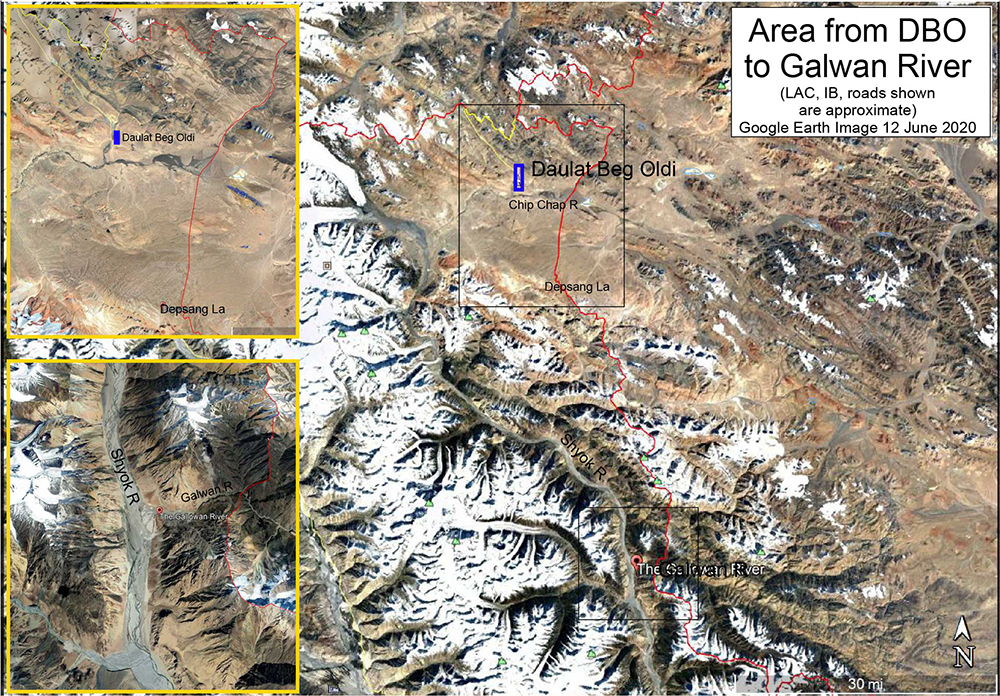

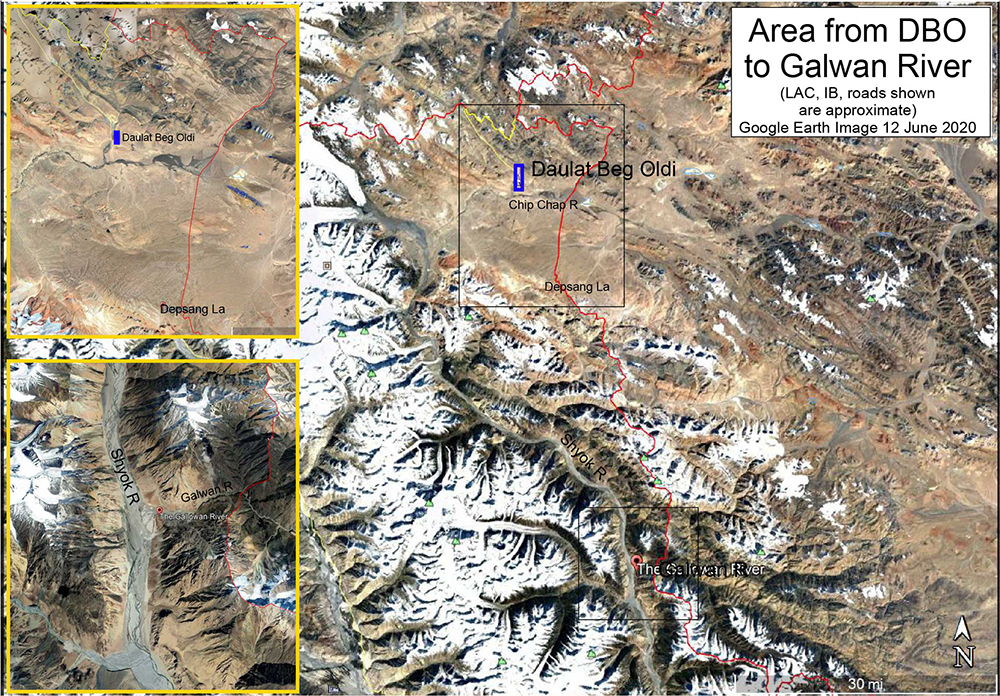

The Chinese too postponed their exercise by a month but when the manoeuvres were carried out, they surprised Indian troops by quick redeployment in the Galwan Valley and the Fingers Area along Pangong Tso lake. The Galwan standoff threatened to cut off a strategic road built last year to connect the Daulat Beg Oldie base and the Karakoram Pass to Leh.

While India carried out mirror deployments by quickly rushing troops from Leh — breaking all Covid-19 protocols — the first movers advantage led to China positioning troops at several strategic points. Internal estimate of Chinese strength at Galwan was 3,400 troops, while 3,600 had built up at the Pangong Tso lake.

Tensions in the region escalated after a May 5 cross-border clash, when Indian and Chinese soldiers came to blows and hurled stones at each other near the Pangong Lake. A similar face-off was reported at Naku La in Sikkim on May 9.

Contested Areas

Both sides had earlier identified 11 of the 23 contested areas on the LAC in Ladakh under the western sector, four in the middle sector, and eight in the eastern sector. Galwan and Hot Spring, sites for the current tensions between the two sides, did not figure in the list of 23 contested areas. Both sides had agreed that Galwan and Hot Spring were ‘settled areas’ and, therefore, it was surprising that the Chinese chose these areas.

Pangong Tso was part of the list. On the northern bank of Pangong lake, India claims that its area is from Finger 1 to Finger 8 and China claims their area to be from Finger 8 till Finger 2. The standoff between the two sides has usually taken place when patrol parties come face-to-face between Finger 4 and 8, which is claimed by both sides.

Depsang Plain

Satellite imagery showed a large number of Chinese armoured vehicles in the Depsang area, near Daulat Beg Oldi, where Indian and Chinese troops had confronted each other for three weeks in 2013, before mutually disengaging.

Reports of a heavy Chinese presence at Depsang, an area at a crucial dip (called the Bulge) on the LAC increased tensions between Indian and Chinese troops.

Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) troops pitched tents in the area, while equipment, light armoured vehicles (LAVs) and a “large number” of tanks could be seen further back in area that China controls.

The Depsang plain is one of the few places in the Western Sector where LAVs would have ease of manoeuvre, so any Chinese buildup there would be a cause for concern.

Pangong Tso

Pangong Tso is a long narrow, deep, endorheic (landlocked) lake situated at a height of more than 14,000 ft in the Ladakh Himalayas. The western end of the Tso lies 54 km to the southeast of Leh. The 135 km-long lake sprawls over 604 sq km in the shape of a boomerang, and is 6 km wide at its broadest point. The brackish water lake freezes over in winter and becomes ideal for ice skating and polo.

By itself, the lake does not have major tactical significance. But it lies in the path of the Chushul approach, one of the main approaches that China can use for an offensive into Indian-held territory.

Indian assessments show that a major Chinese offensive, if it comes, will flow across both the north and south of the lake.

The trigger for the face-off was China’s opposition to India laying a key road in the finger area around Pangong Tso Lake, besides construction of another road connecting Darbuk-Shayok-Daulat Beg Oldie road in Galwan Valley.

China was also laying a road in the Finger area, which was not acceptable to India. Military reinforcements including troops, vehicles and artillery guns were sent to eastern Ladakh by the Indian Army to shore up its presence in the areas where Chinese soldiers were resorting to aggressive posturing.

The situation in eastern Ladakh deteriorated after around 250 Chinese and Indian soldiers were engaged in a face-off on May 5, which spilled over to the next day before the two sides agreed to “disengage”. However, the standoff continued.

Towards the south of Pangong Tso, forces physically scuffled over denial of patrolling at Sirijap on May 5-6 and on May 11.

At the Pangong Tso lake the Chinese side seemed to be attempting a shift of the LAC by moving in by 2-4 kms along the Fingers area. A new bunker complex came up and Indian patrols that used to go to the West were blocked. High-resolution satellite images of the Pangong Tso area in Ladakh showed the Chinese had built “substantial” structures between Finger 4 and Finger 8, changing the status quo.

Chinese used light vehicles on the road to patrol up to Finger 2, which has a turning point for their vehicles. The PLA also brought more boats into the Pangong Lake and built bunkers. The Chinese have also black-topped the road between Finger 8 and Finger 4. The PLA had constructed a dirt track in this area in 1999 when Indian units were pulled out of this area during the Kargil conflict.

Chinese border posts were at Finger 8. Around six years ago, the Chinese had attempted a permanent construction at Finger 4 which was demolished after Indians strongly objected to it.

The Indian side patrols on foot, and before the recent tensions, could go up to Finger 8. The fracas between Indian and Chinese soldiers earlier this month happened in this general area at Finger 5, which led to a “disengagement” between the two sides. The Chinese have now stopped the Indian soldiers moving beyond Finger 2.

Galwan River Valley

The PLA pitched tents in at least three locations, including two in the Galwan Valley, where the showdown leading to the 1962 war had started. Here, troops were engaged in skirmishes at the junction of Galwan and Shyok rivers, Patrolling Point 14, 15, and 17 and at Gogra Top.

The point where the Galwan river joins the Shyok river is where the LAC runs closest to the Shyok-DBO road. The Chinese occupied heights overlooking the river junction thereby threatening the link to DBO.

North Sikkim

After the 1986-1987 Sumdorong Chu incident in Arunachal Pradesh, it was more than 30 years later, at Doklam, on the Bhutan border that Chinese transgression led to both sides moving up a brigade-sized force (around 5,000 troops) to the LAC.

On May 9, Chinese and Indian forces reportedly engaged in a separate clash where Sikkim meets Tibet. Four Indian and seven Chinese soldiers suffered injuries in a scuffle at Naku La that involved roughly 150 soldiers in total. At least 10 soldiers from both sides sustained injuries in the incident.

The Army units at Binnaguri, Hashimara and few other places were upstaged and underwent acclimatisation in Sikkim for further deployment.

Past Pattern

The Chinese first made encroachments into the 45-km long Skakjung pastureland in Demchok-Kuyul sector. This resulted in local Changpas of Chushul, Tsaga, Nidar, Nyoma, Mud, Dungti, Kuyul, Loma villages gradually losing their winter grazing that sustained 80,000 sheep/goats and 4,000 yak/ponies every winter.

Ladakh’s earlier border lay at KeguNaro — a day-long march from Dumchele. Starting from the loss of Nagtsang in 1984, followed by Nakung (1991) and Lungma-Serding (1992), the last bit of Skakjung was lost in 2008. The PLA followed the nomadic Rebo routes for patrolling in contrast to Indian authorities restricting Rebo movements that led to the massive shrinking of pastureland and border defence.

By the 2000s, the PLA’s focus shifted to desolate, inhospitable Chip Chap which remains inaccessible until end-March. After mid-May, water streams impede vehicles moving across Shyok, Galwan, and Chang-Chenmo rivers leaving only a month and a half for effective patrolling by the Indian side.

Easier accessibility allowed the PLA to intrude into Chip Chap with impunity during July-August during the 21-day Depsang stand-off in 2013, when Burtse became a flashpoint, the PLA set up remote camps 18-19 km inside Indian territory.

The Shyam Saran Report of August 2013 made a chilling revelation of India having lost 640 sq km due to “area denial” set by PLA patrolling. The government denied the report, but Chinese soldiers virtually prevented Indian troops from getting access to Rakinala near Daulat Beg-Olde (DBO) where the IAF reactivated the world’s highest landing strips in 2008.

Comments

China and India have built an elaborate framework of confidence-building measures for border management. In 2019, they unveiled a new program to attempt “coordinated patrolling” for the first time in a relatively peaceful portion of the LAC in eastern Arunachal Pradesh.

The latest confrontation has laid bare gaps in the implementation of confidence-building measures agreed upon by both sides, such as strengthening the mechanisms for sharing information and resolving disputes through dialogue. A major hindrance is the lingering trust deficit, which is attributed to some thorny issues: China’s continuing military and diplomatic support to Pakistan and the two neighbours’ contesting claims over Arunachal Pradesh and Ladakh.

Sino-Indian Military Border Talks

In an effort to resolve month-long standoff along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in Ladakh, on 6 June, Indian and Chinese armies held Lt Gen-level talks. While the Indian side was led by Lt Gen Harinder Singh, the GOC of Leh-based 14 Corps, the Chinese side was headed by the Commander of the Tibet Military District. The talks between the military commanders of both armies took place at the Border Personnel Meeting Point in Maldo. This meeting point is on the Chinese side of the LAC in Eastern Ladakh.

The military level talks came close of the heels of diplomatic talks which took place on 5 June. At the diplomatic talks, according to the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), both agreed to handle their “differences” through peaceful discussions.

After 12 rounds of talks between the local commanders of the two armies, and around three rounds of talks at the level of the major general-rank officials, there were no tangible outcomes. This led to the Lt Gen level talks on 6 June.

At the military talks, India insisted on restoring status quo ante in Galwan Valley, Pangong Tso and Gogra in eastern Ladakh.

The Indian agenda for the meeting centred around restoration of the status quo ante on the LAC to April-end — before China diverted its forces from an ongoing military exercise towards the Indian side. This translated into an Indian insistence on withdrawal of all Chinese troops from Indian territory – though it falls between the different ‘perceptions’ of LAC of both sides – and removal of all constructions undertaken by the Chinese in the same area.

The Indian side also raised the issue of the limits of patrolling by both sides, as conducted hitherto, and sought restoration. In the Pangong Tso area, Indian troops were not being allowed by the Chinese to patrol up to Finger 8.

India also sought a mutually agreed progressive reduction of heavy military equipment, such as artillery guns and tanks, from the rear areas of both sides. This was seen as a confidence-building measure to reduce tensions and a first step towards creating a more conducive environment for further talks.

The Indian side also wanted China to stop objecting to infrastructure development activities well within Indian territory. The opening of the 255-km long Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldie road created opportunities for lateral roads, which led to objections from the Chinese.

The Indian Army’s official spokesperson said, “To address the current situation in the India-China border areas, officials of both countries remain engaged through the established military and diplomatic channels.”