Third term as party chief is a prelude to his extension as Chinese President

The most significant outcome of the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC), which ended on 23 October, is the re-election of Xi Jinping for a record third term as the general secretary of the party. This is a prelude to his extension as the President of the People’s Republic and the Chairman of the powerful Central Military Commission for yet another term, and possibly for life.

Deng Xiaoping, who led China following the disastrous decades of Maoist excesses, pushed the CPC to adopt the norms of collective leadership that led to presidential terms being limited to two and put in place an informal retirement age of 68. Xi has pushed all these conditions aside to emerge as an all-powerful figure after the last 19th Party Congress did away with presidential term limits.

Xi’s power is evident from the two key political ideas introduced into the CPC constitution last week. “Two establishes” calls on the party to recognise Xi as the “core” and to accept his ideas as a key tenet of the party rule. The “two safeguards” calls on the CPC to protect Xi’s status and safeguard the party’s leading role in China.

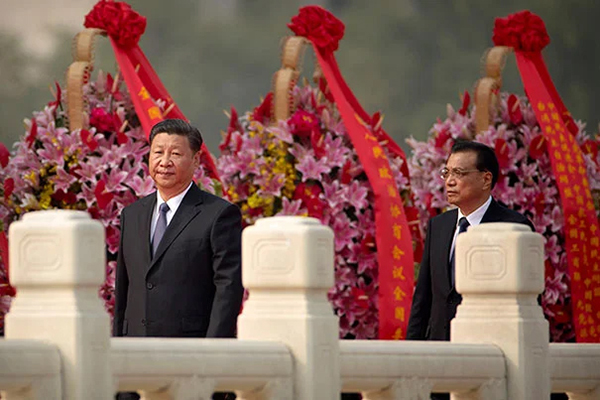

Xi’s centralisation of power was visible on Sunday, when he paraded China’s apex ruling team, the Communist Party’s Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC) on the dais at the 20th Party Congress on its closing day. They are all his key allies, signalling that loyalty was the key criterion for their appointment.

No. 2 to Xi in the CPC’s apex body is Li Qiang, who is expected to replace Li Keqiang as Prime Minister in March 2023 when the National People’s Congress meets to select a new government. Li Qiang’s current job is as chief of the CPC in Shanghai. Among the other new appointees are Cai Qi, party chief of Beijing, Ding Xuexiang, former chief of staff of Xi, and Li Xi, party leader from Guangdong.

Premier Li Keqiang and Vice-Premier Wang Yang were both dropped from the PBSC. Both are 67 and could have been considered for another term. Another 67-year-old leader, Wang Huning, an associate of Xi was re-elected. Vice-Premier Hu Chunhua, who was once considered a potential successor, failed to make it to the PBSC and was actually dropped from the Politburo itself.

In the lineup of the new leaders, what is significant is dropping of leaders like Li Keqiang, who is a trained economist. Another two important figures — People’s Bank of China Governor Yi Gang and banking regulator Guo Shuqing — have been dropped from the new Central Committee. There is speculation that leaders who take a more liberal approach to economic policy have been dropped.

Having done away with the only significant constitutional limitation on the personal power of a leader attempted by Communist China, the fears are that Xi will also shed restraints in the exercise of that power. He has been known for policies of nationalism, enhancement of the role of the CPC in the everyday life of China, a hard line on Taiwan and confrontation with the West and other countries like India.

There is every expectation that Xi will double down on his policies relating to the economy and security, both of which were important themes of his work report to the Party Congress on its very first day. In the ensuing week, some of the issues were written into the CPC’s constitution. The report provided a policy blueprint for the coming five years.

In his two-hour speech, Xi spelt out the CPC’s priorities on economic policy and security. There were new sections on science and education, signalling the increased emphasis on their role in China’s plans for the future. The essence, according to observers, was on the “Chinese characteristics” of modernisation and governance.

Xi’s emphasis on the economic front was a call to promote the development of science and technology and at the same time orient Chinese economic growth towards a more equal distribution as indicated by the slogan he gave in 2021, calling for “common prosperity”. He has, however, made it clear that the overall policy of promoting economic growth will continue.

There was a significant emphasis on security and a veiled attack on the US, which was attempting to “blackmail, contain, blockade and exert maximum pressure on China.”

Xi boasted that China would have a world-class army by 2027 and said besides “strategic deterrence” (nuclear), “new domain forces with new combat capabilities” would be introduced. From India’s point of view, there was a reference that the PLA modernisation would “shape our security posture, deter and manage crises and conflicts and win local wars.” There is little doubt that this refers to China’s issues with Taiwan and India. The screening of clips of the Galwan clash for the Congress delegates confirmed that India is very much in the minds of decision-makers in Beijing.

The notion of term limits for high offices goes back into history, and so does the opposition to it by strong men like Julius Caesar and Napoleon. Modern experience suggests that in eight to 10 years of office, leaders get jaded. This is evident from the record of office of leaders like Russian President Vladimir Putin, Turkey President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, North Korea’s Kim Jong-un and numerous African heads of government.

There was a certain wisdom in Deng Xiaoping’s effort to promote collective leadership and check the power of a single leader. Those restraints have been removed by Xi and China may once again have to confront the consequences of being ruled by a supremo who has no check on his authority.