The Air-India Express crash at Karipur International Airport, Kozhikode, on 7 August 2020 and the role played by flying-experience of the pilots involved necessitates examining aviation safety aspects.

Aviation is by far the safest mode of conveyance available to mankind. With a death-rate of 0.05 per billion km of travel, aviation beats other forms of transport by about 100 times. This high safety of air-travel is attributable to remarkable strides in technology making aircraft immune to systems-failures. Dual, triple and even quadruple redundancies are built into critical systems like fuel-supply, lubrication systems, landing and braking systems, flight-control and navigation systems, etc, to rule out failure. Monitoring of aircraft maintenance and aircrew training by regulatory authority ensures the aircraft and flying-crew are fit-for-flying. An airlines’ reputation rests on its safety record; not in the appearance of its air hostesses or in the quality of wine served.

Two air-crashes, in rapid succession in March and July of 2014, both caused by extraneous factors, marred the image of Malaysian Airlines and almost killing the airline. Similarly, Air India and its subsidiaries have fast become the airline-of-last-resort for most passengers.

The big problem with aviation accidents is survivability. While road or train accidents take place more frequently and in larger numbers, they have a higher survivability. Even shipping accidents afford time for rescue teams to save lives. Air crashes are violent and fiery with only miraculous survivors.

In as technologically advanced a field as aviation, greater the experience of the pilots, higher should be the assurance of safety. While experience is necessary in all fields, it becomes critical in fields impacting safety of humans or when stakes are high, as in surgery, aviation, shipping, litigation, etc. People are justifiably averse to retaining less experienced professionals for crucial situations. While one has a choice of selecting a professional in surgery or litigation; such choice is not available in aviation, shipping and public transport sectors. One must rely on the regulatory authorities for professional competence, currency, physical fitness and mental alertness of the crew responsible for human lives in their care.

Experience of a pilot is counted in terms of flying-hours. A person becomes a civil pilot at around 25 years and retires at 65 – a professional life-span of 40 years. During this time, a pilot may accumulate 25,000 to 30,000 flying-hours.

ALSO READ MILITARY HISTORY : A History of Military Aviation in India 1901-1947

Modern aircraft have become very safe and pilot friendly. Automation has taken over almost all the crucial functions in the cockpit. Flight-planning, weight-balance check, critical speed calculations, route-navigation, departure and arrival protocols and even take-off, route-flying and landing are all computerized and automated. The ease of flight operations, coupled with a high level of accuracy of auto-pilot systems, has resulted in few system failures and negligible operational errors. Protracted working in such a reliable and fail-safe environment, for years, has a dulling effect on the edgy alertness required of pilots.

Highly Experienced Pilots

Modern pilots may go for thousands of hours of incident-free flying and many may complete entire careers without facing a single system malfunction. Most pilots face emergency situations only in simulators during initial or refresher training. This is in sharp contrast to the early years of aviation, say from 1950s to 1980s, when almost every pilot experienced some or the other malfunction or abnormal situation in the cockpit. The doctrine of hands-off flying in modern aircraft, even for take-off and landing, has further eroded the skill of hands-on flying by pilots. It is, thus, unfair to expect modern pilots to suddenly take over controls and fly an airplane in an emergency. A person on crutches for a long time cannot be expected to shed them and suddenly start running. Motor-skills require constant and repetitive practice. Alertness to possible abnormalities and thinking ahead are cornerstones of good pilots.

There are pilots with over two decades and over 20,000 hours of experience who have not faced a single in-flight emergency, except on a simulator. There is a great difference between a simulated emergency and an actual one. Not every pilot is a Chesley Sullenberger (Sully), who coolly glided his fully-laden Airbus A-320 on the Hudson River on the outskirts of New York, saving 155 souls-on-board. The degree of professional cool displayed by Sully and his novice First Officer, Jeff Skiles, after losing both engines to bird-ingestion, soon after take-off at 3000 ft, over the Manhattan concrete jungle, is the stuff of a Dhoni, cricket world’s Captain Cool. Human temperatures drop in an emergency; some freeze while some remain cool. Most pilots would have frozen or attempted to land at the nearest runway, crashing in one of the densest urban populations in the world. Sully is a white example of a pilot who used his vast experience to reject ATC advice and opted for the safety of a river that afforded a safe ditching over an iffy return to the nearest airfield, Teterboro. There is no dearth of black examples of pilots who have crashed when faced with lesser emergencies, killing many and destroying aircraft.

Mangalore and Kozikhode Crashes

No lessons seemed to have been learnt by Air India Express, International Airports Authority of India (IAAI) and Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA), the aviation regulator in India, after the disastrous crash at Mangalore International Airport on 22 May 2010. Almost a decade later, a similar crash takes place at Karipur International Airport, Kozhikode on 7 August 2020.

The similarities of these accidents are striking and point to the inadequacy of “pilot experience” as a yardstick for flight safety in both cases.

• Both accidents were of Air India Express.

• Both on Boeing 737-800 aircraft.

• Both took-off from Dubai.

• Both crashed on table-top runways.

• Both had serviceable aircraft.

• Both had deep landings, ie, they did not touchdown at the beginning of the runway, leaving less runway available for braking and stopping.

• Both overshot the runway and fell down the table-top.

• Both aircraft wreckages were found in “go-around initiated” condition, ie, the pilots had initiated a take-off at a very late stage.

The differences in the two accidents were: the weather was marginal and the runway was wet in the Kozhikode accident, whereas, the Mangalore accident did not have this problem. The pilot-in-charge (PIC) of the Mangalore accident, Captain Zlatko Glušica, a Serbian national, was a last-minute change to operate the flight and may not have been fully rested or mentally ready. Capt Glušica stubbornly continued with an overshooting approach, despite repeated advice of his First Officer, Capt HS Ahluwalia, to abandon the approach and go-around, touching down 5200 ft down a 8000 ft runway, leaving just 2800 ft to stop the aircraft. The realization that the aircraft would not stop on the runway also came too late and the intended go-around action failed. Whither pilot experience?

In the Kozhikode accident, while the weather was marginal and the runway wet, the visibility and cloud base were within the prescribed minima for landing. The runway in use, Runway 28, was changed to Runway 10 at the pilot’s request. The pilot was well-versed with the airfield, having previously landed there 27 times, including 10 times in 2020. An experienced pilot would have factored in the obvious tail-winds on the approach on Runway 10 and would have planned a lower approach and a threshold touchdown to ensure maximum braking distance available on a wet runway with a negative slope. The runway, at 8003 ft, was long enough for an A-320 to land in those conditions. There was no cause for panic as the aircraft was serviceable with enough fuel for multiple approaches or diversion to the many airfields in Kerala.

Pilots are trained for much worse configurations during simulator training and flight checks. Why an experienced pilot would continue an approach in tail-wind conditions on a downward sloping wet runway well past the middle-marker of the runway is more than sanity can justify. Capt Deepak Sathe, with over 10,000 hours on Boeing 737s, in addition to his enormous flying experience in the Indian Air Force (IAF), laid to waste all his experience and knowledge of the aircraft, the airfield and his own skills when he touched down at the 5200 ft mark of the 8003 ft runway. He still had about 2000 ft of runway to initiate a safe go-around and make another approach or to divert to Kerala’s many airports nearby. He, perhaps, set too much store by the short-landing-performance of his aircraft. The decision to go-around was so late that the jet-engines did not have time to overcome inertia. This decision-making of Capt Sathe cost him his own life along with those of his young First Officer Akhilesh Kumar, whose wife was expecting their first child in Sep 2020 and 16 other unfortunate passengers, while injuring a hundred more. Capt Sathe was not being reckless; he was simply responding to his inner voice that had benumbed his anxiety. Years of safe landings had made him immune to the reality and effect of emergencies.

Measure of Experience

On 4 November 2015, Capt E Samuel of Pawan Hans Ltd, with over 20,000 hours on Dauphin helicopters, close to a world record, could not handle the first real emergency he faced in his life, while imparting off-shore night-training to a pilot at Bombay High. He had become so comfortable in the cockpit, he was known to throw the helicopter around during revenue flights in Bombay High, the only field of operation seen by him in over two decades in Pawan Hans Ltd. This is a case of a pilot who had flown only one type of aircraft in only one sector of operation and in only one type of off-shore operation for over 20 years. Complacency, a sworn enemy of safety, was inevitable. The actual cause of the accident is a mystery as the helicopter crashed into the sea at night, killing both pilots, with no wreckage found for months. What was the use of all that experience, counted in years and flying-hours? Complacency negated experience due to ease of operations and high reliability of the machine. There are numerous such examples worldwide.

Compare the flying experience of these pilots to that of Wg Cdr (Retd) SS Dholia of IAF. He experienced engine-failure on his first solo flight, in a single-engine HT-2 at Elementary Flying School, Bidar in the late 1970s. He safely brought the stricken aircraft down, much to the awe and applause of his mates and instructors. Within about 8 months, he met a similar fate on his first solo flight on Kiran aircraft in Air Force Academy, Dindigul. Again, he managed to glide the aircraft safely on the runway. He was a flight cadet then. Had he been an IAF officer, he would have earned Vayu Sena Medal with Bar for these two safe retrievals of crippled aircraft. His flying experience at the first incident was 9 hours and at the second one, about 60 hours. Such a pilot, as Wg Cdr Dholia, was far more experienced in the adversities of aviation at 60 hours stage than those who meet no serious incident for decades. Events make for greater experience than mere passage of time.

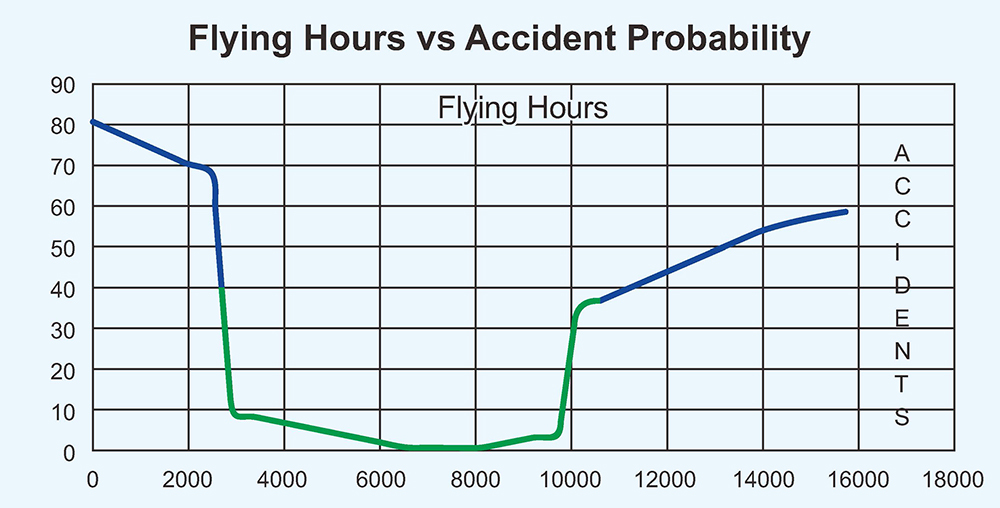

Measure of experience in motor-skill jobs, especially aviation, needs a different yardstick. It can no longer be measured in calendar experience, fraught with false assurances, showcased by the many accidents worldwide. What is experience that is purely fair-weather and with all-systems-go? Calendar experience needs to be tempered with event experience, where events are cockpit experiences of abnormal nature that shake a pilot out of his reverie. If events do not happen in a pilot’s life, these should be manufactured like change of aircraft, change of operational area, breaks in flying-duties, etc. The idea is to erase the numbing effect of complacency that creeps in due to prolonged hunky-dory operations. One should remember the Bathtub Graph of Flying Hours vs Accident Probability.

Those in the ascendant stage of the above graph need to be monitored and an event manufactured in their career to reposition them back in the safety of the 3000 hours to 9000 hours range.

Nowadays, a human being is the weakest link in the chain of aviation security. Pilots are urged, during simulator training, to avoid handling the aircraft during critical stages of landing for the reputation of the aircraft. Pilotless aviation tried and tested since 1970s has established the redundancy of pilots in aircraft cockpits. UAVs, drones and space vehicles are doing famously without a human on board. Now, pilots crew commercial flights more for the psychological satisfaction of passengers than for any piloting need. The technology is now filtered to road transport with driverless cars a reality.

In sum, a classical experienced pilot, without abnormal events in his aviation career, is a ticking time-bomb just waiting for a critical abnormality before it explodes. Aviation regulators, operators and flight-safety managers need to find a method to defuse these bombs.

This is with regard to Col Shailendra Sharma’s article FLIGHT SAFETY: Pilot Experience is No Guarantee of Safety. Would like to know the source of the “bath tub” graph that has been shown with respect to accident probability Vs Pilot experience. Also, if Col Sharma would like to share his e mail id, would be appreciate. Thanks .