The seeds of the war which led to the creation of the state of Bangladesh in 1971 were sown in 1947 when East and West Pakistan were created by the partition of India. United only by adherence to the Muslim faith, they were separated from each other geographically by 1000 miles and immeasurably by race, culture, language and economics.

Though the East provided 75 per cent of the foreign earnings and exports, the reins of power were almost exclusively in the hands of West Pakistanis. Initially, Pakistan called itself a democracy, but effectively the country was run by the army, the President from 1958 to 1969 being Field-Marshal Ayub Khan.

The arrest, in 1966 of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, leader of the Awami League and the outstanding political figure in East Pakistan, convinced his supporters that limited autonomy was no longer a realistic aim and that total separation was the only answer. In March 1969, Ayub Khan, having lost all semblance of popular support, gave way to General Yahya Khan, who, in December, 1970, held an election in which the Awami League won a clear majority, whereupon Yahya announced the indefinite postponement of the opening of Parliament. Rioting broke out in East Pakistan; on 25 March, 1971, the Sheikh was again arrested and the following day the unofficially styled ‘Bangladesh’ seceded from the Government of Pakistan by unilateral declaration. Yahya then sent Lt Gen Tikka Khan to East Pakistan with orders to ‘sort them out’. Thereafter, the army went on the rampage and some estimate that as many as a million civilians were murdered.

Refugees poured into India and those who remained, having nothing to lose, flocked to join the Awami League’s militant resistance organization, the Mukti Bahini, including most of the 70,000 locally recruited members of the armed forces. By August, six million refugees had fled to West Bengal, an intolerable burden for the Indian Government, whose armed forces were now actively preparing to come to the aid of the Mukti Bahini. This was not practicable until November when the monsoon would be over and the ground hard enough to allow large-scale operations, while the onset of winter would close the Sino-lndian frontier and inhibit interference from China.

There were several clashes between Indian and Pakistani forces on the East Pakistani border in October and November, when the latter crossed the frontier in ‘hot pursuit’ of the Mukti Bahini, finally leading, on 3 December, to the outbreak of open warfare on two fronts.

Save for the hilly tracts of Chittagong, East Pakistan was a riverine country. The river Brahmaputra flows through the centre to divide the country into two. Both these halves are further dissected by the Ganga river in the west and the Meghna river in the East. Besides, there are many other water channels and rivulets in between. On the few arterial roads which exist there are only two bridges across these mighty rivers – the Hardinge Bridge over the Ganga and the bridge across the Meghna at Ashuganj. Inland waterways cater for most of the surface communications within. All in all, East Pakistan terrain was excellent for defensive operations.

Towards the end of April 1971, the Indian government gave the first indication of a possible military intervention in East Pakistan to Gen SHFJ Manekshaw, the Chief of the Army Staff. For a variety of sound strategic military reasons he advised the government against a hasty and indecisive military venture. The government too had other political compulsions and better sense prevailed. Consequently, the Army Chief set in motion a well-conceived plan to prepare for an all out war. To avoid getting bogged down in the riverine terrain, it had to be well after the monsoons and to preclude possible Chinese intervention, it had to be nearer the winter by when the passes on the high Himalayas close.

Shortages in manpower and equipment were made up steadily. The army’s resources, particularly the engineer effort and the bridging equipment, were judiciously allotted to the two widely separated western and eastern theatres. Formations were affiliated to the newly raised HQ 2 Corps. Territorial Army units were embodied and reservists were called up. Additional communication zone units were also raised to ensure better logistics support.

All this while Eastern Command was abuzz with hectic activities. In April 1971, it had only one division earmarked for a possible role in East Pakistan. Two more divisions were pulled out from their counter insurgency commitments. Three divisions were milked out from those having their role in Sikkim and in Arunachal Pradesh. One more division, otherwise intended for the Uttar Pradesh-Tibet border, was also placed under the Command. Operational control of all Border Security Force units deployed along the East Pakistan border was handed over to Eastern Command. All formations, operationally oriented either for a role in the mountains or for counter-insurgency operations, were trained and prepared for the impending riverine operations. Measures to create the necessary logistics infrastructure, to support the operational contingencies, were initiated. Operational plans were evolved, coordinated with the Navy and the Air Force and were finalised.

In the event of war, Pakistan had apparently visualised an Indian offensive attempting a shallow penetration, to install the Provisional Bangladesh Government. They had also counted on American support and Chinese intervention to restrain India. Hence, Pakistan’s overall defensive philosophy was to cause maximum delay by holding fortress like strong defences on all routes of ingress along the border. In consonance with their threat analysis, deployment towards the west and the north was to be heavier. For this defensive plan, Lt Gen AAK Niazi had a strength of about four divisions and seven wings of paramilitary forces. 9 Pakistan Infantry Division, with its HQ at Jessore, was to guard the western approaches. 16 Pakistan Infantry Division was responsible for the Dinajpur-Rangpur salient towards the northwest and had its HQ at Nator. The northern sector of Mymensingh was considered the least threatened and had only about a brigade deployed to defend it. Wary of the preparatory activities in Tripura, the eastern approaches to Dacca were being guarded by 14 Pakistan Infantry Division located at Comilla. Rings of defences had also been prepared around Dacca. Thus, hoping to fight set piece defensive battles of attrition, Niazi had opted for orthodox positional warfare and could be faulted for rigidity.

In contrast, Lt Gen JS Aurora, the GOC-in-C, Eastern Command, had a plan that was bold and had streaks of originality. It sought to defeat the very premises of the defender’s strategy. In essence there were to be three thrusts by 2, 33 and 4 Corps from the west, north and the east, respectively. Each Corps was to contain the enemy strong points with small forces while the larger components were to bypass these for objectives in depth. All three Corps had planned to maintain speed of action, without tactical pauses, for a dash to Dacca before the defences around it could be occupied. The enemy was to be forced to react to Indian moves throughout. That is where superior generalship lay.

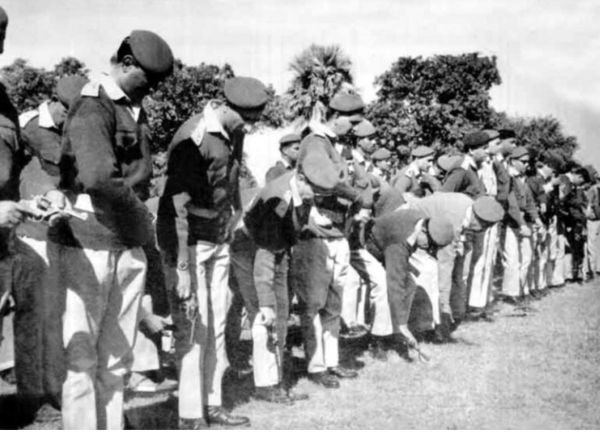

Mukti Bahini

After Lieutenant General Tikka Khan’s crack down, many officers and men from the East Bengal Regiment, East Pakistan Rifles and the police, had tried to raise an armed rebellion. Their disjointed efforts did not create the desired impact and they gradually trickled into India. Many of them had come with their weapons. They provided the nucleus for the Mukti Bahini. Trained and equipped by the Indian army, they were meshed into the operational plans of the formations of Eastern Command. Till August 1971, motivated bands of Mukti Bahini had operated along the border or had ventured only a few kilometers across. By October 1971, however, the Mukti Bahini had stepped up its activities to tie down sizeable Pakistani forces along the border and on many static duties well in depth.

Tension mounted further as the Pakistani forces resorted to unprovoked firing on Indian posts and civilian targets alike. Between November 20 and 23, 1971 fierce battles were fought at Garibpur, around Hilli, and at Atgram. The commanding officers of all the three battalions which fought these actions – 14 Punjab, 8 Guards and 4/5 Gorkha Rifles – went on to earn Maha Vir Chakras.

War broke out on December 3, 1971. On that day the Eastern Command was also responsible for the northern borders with China and for the ongoing counter-insurgency operations in many eastern states. The total forces under the Eastern Army nearly touched the half million mark.

Eastern Front Timeline

3 December Pakistan Air Force attacks Agartala airfield.

4 December India launches integrated ground, air and naval offensive. Aircraft from the carrier Vikrant bomb airfield at Cox’s Bazar. Dacca bombed every 1/2 hour.

5 December Indian Army links up with Mukti Bahini and enters E. Pakistan from five directions.

6 December India announces recognition of independent state of Bangladesh.

5-14 December Indian troops occupy East Pakistan towns on:

5th – Akhaura, Laksham

6th – Feni

7th – Sylhet, Jessore

8th – Magura, Comilla, Brahman-baria

9th – Chandpur, Daudkandi

10th – Bhairab Bazar

11th – Noakhali, Nasirabad, Kushtia

12th – Narsingdi

14th – Bogra

14 December Indian artillery starts shelling Dacca. Garrisons now still holding out only at Dacca, Rangpur, Dinajpur, Khulna, Barisal, Chittagong and Mainamati (a fortified cantonment outside Comilla).

15 December Indian forces close on Dacca from all sides.

16 December General Niazi signs surrender document for Pakistan, though fighting continues in the Khulna and Sylhet areas until 17 December. Excerpted from yet-to-be-published “The Fighting Spirit: An Illustrated Account of the Indian Army’s Operations in the Twentieth Century” by Maj Gen RK Arora.