The Pakistani high command has, for a number of years, nursed a pipedream about launching a massive, surprise offensive deep into Indian territory—spearheaded by armoured formations, a la Moshe Dayan. Unfortunately for them, they do not have a Dayan; nor are Pakistanis Israelis: besides, India is not a restricted piece of territory like the Sinai desert in which a thrust such as the above could, even if successful, prove instantly decisive.

By the end of November, the Pakistani high command must have realised that the Indian Army had deployed in full strength on the west, its infantry divisions backed up by a number of armoured brigades—besides the formidable 1st Armoured Division. As for its own forces, the two divisions that Pakistan had begun to raise in May 1971 to replace the divisions sent to the eastern wing were still below strength and not fully operational. No one but an incurable optimist would, in those circumstances, hope for the cherished breakthrough to materialise. And yet that is exactly what they attempted—and with incredible ineptitude.

Pakistan launched a pre-emptive strike on a number of Indian airfields—Srinagar, Avantipur, Pathankot, Uttarlai, Jodhpur, Ambala and Agra – at 5.45 pm on 3 December 1971. The strikes were clumsy. Not a single Indian aircraft was lost on the ground. Within 24 hours the Indian Air Force (IAF) had broken the back of the Pakistani Air Force (PAF) through counter-strikes.

The Indian Air Force went into action later that night and continued mounting operations till they reached the peak of 500 sorties per day — a world record. The IAF attacked Chanderi, Shorkot, Sargodha, Muri, Mianwali, Marur (Karachi), Risalwalla (Rawalpindi) and Changa Manga (Lahore). Over 25 aircraft were hit.

After the first abortive series of strikes the PAF ceased to be a serious air threat. By the evening of 4 December, the IAF had established air superiority.

Land Forces

The Pakistan Army in the West consisted of about ten infantry divisions (two of them newly raised) a few independent brigades, two armoured divisions and an independent armoured brigade. The grouping was as follows:

Kashmir Sector

• 12th Pakistani Occupied Kashmir (POK) Division in the northern sector

• 23 POK Division on the Kotli-Poonch front.

• II Pak Corps, HQ In the Sialkot sector: Sialkot

8,15 and 17 Infantry Divisions

6 Armoured Division.

• IV Pak Corps, HQ Lahore, in the Central sector

10 and 11 Infantry Divisions

8 Independent Armoured Brigade.

• I Pak Corps, HQ Mooltan, in the Mooltan sector

7 and 33 Infantry Divisions,

25 Infantry Brigade

1 Armoured Division.

• 18 Infantry Division, in the Southern sector

• Two armoured regiments

From these dispositions, it was appreciated by our high command that the most likely sectors where the Pak army-would attempt offensives would be, firstly, on the Sialkot front, with the aim of cutting either the Jammu-Poonch or the Pathankot-Jammu road links to isolate our forces: and secondly, a thrust by I Pak Corps in the southern Punjab. The latter could be the much vaunted “deep Israeli-type thrust”.

Indian Forces, only marginally superior, were grouped as follows:

• Western Command (Lt Gen K.P. Candeth).

• Three army corps (Lt Gen Sartaj Singh, Lt Gen N.C. Rawlley and Lt Gen K.K. Singh).

• Army HQ reserve.

• Southern Command (Lt Gen G.G. Bewoor), responsible for the Rajasthan front.

Jammu & Kashmir Theatre

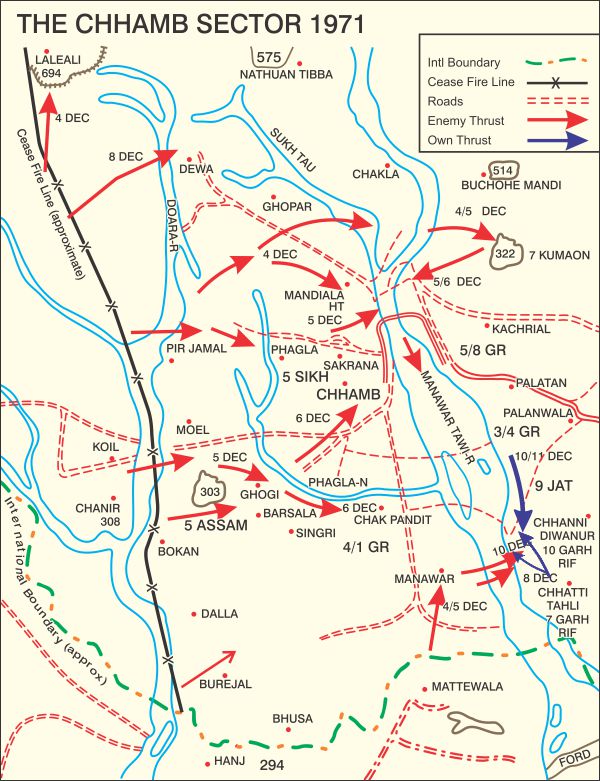

The first Pakistani offensive was launched at 8.30 pm on 3 December, against the Indian Army’s Poonch and Chhamb sectors. The aim was to capture a piece of Kashmir territory by a pincer movement. It failed miserably.

An “Azad” Kashmir infantry brigade launched an attack against Poonch from the direction of Kahuta in the north-west, while commandos infiltrated behind the Poonch area to cut the road link.

The attack was launched with determination but the IAF pounded them in the forests north-west of Poonch. The enemy decided to call off the attack.

The second attempt on the night of 9/10 December, was pre-empted by the IAF – it strafed them in their assembly areas.

The Indian forces now launched the counter-offensive. A brigade column was moved towards Hajiian to dominate the Poonch-Kotli road. By 16 December, most parts of the road had been secured.

In the Chhamb sector, the Indian forces were at a slight disadvantage. The Indian defences, based on the line of the Munnawar Tawi river, had covering positions to the west — only 50 miles from the Pak Army’s base at Kharian. In 1965, the Pakistani forces had scored a major success here.

The story of the Battle of Chammb Jaurian will be covered in a later issue of IMR.

In the rest of the J&K theatre, Gen Sartaj Singh, the Corps Commander, aimed at removing the tactical disadvantages of the alignment of the Ceasefire Line (CFL), by capturing dominating heights and denying the enemy easy routes for infiltration.

In the Kargil sector, this entailed the capture of about 15 enemy posts located at heights of 10,000 feet and more in severe weather and terrain conditions.

In the Tithwal sector, the threat to the Indian lines of communications from a large salient of Pak-held territory on the east bank of the Kishenganga river, west of Tut Mari Gali pass, was cleared.

Similarly, in the Uri sector, where the Haji Pir salient provides easy infiltration access to Gulmarg, Indian forces captured posts in the Tosh Maidan and neutralised the threat.

Punjab Sector

The Pakistanis made limited gains in small enclaves of Indian territory located on the far side of rivers or obstacles. So did the Indian forces.

Of the three bridges over the rivers Ravi and Sutlej where they form the Indo-Pak boundary, the only one that lay in Indian territory was the Hussainiwalla bridge near Ferozepur.

A small Indian enclave on the far bank of the river was attacked by the Pakistani forces on the night of 3/4 December. Fighting a delaying action, in which the Pakistanis lost 18 tanks, the Indian garrison made a pre-planned withdrawal to the east bank of the river — during which the bridge itself was heavily shelled and damaged by the enemy.

In response, Gen NC Rawlley, the Corps Commander, ordered an offensive to capture the Sehjra salient, northwest of Ferozepur. This salient posed a threat not only to Khem Karan but also to the Harike bridge further up the Sutlej.

The attack was to go in on the night of 5/6 December. The attack came as a complete surprise to the enemy. Indian troops took an approach along the open and sandy river-bed leading to a twenty-foot escarpment behind which the Pak defences were located, which was unexpected, with the result that Sehjra was soon captured and the threat to Khem Karan and Harike removed.

Indian forces also attacked and captured the Pak enclave on the eastern side of the Ravi guarding the Dera Baba Nanak bridge on December 6/7. This enclave was strongly fortified with concrete pillboxes and bunkers along the bund, mortar positions and high observation towers. The Indian assault from an unexpected flank, after several feints from a different direction, unbalanced the enemy. By the morning of 7 December, the enclave was in Indian hands with control over the bridge.

Jammu & Kashmir Theatre

Pakistan’s II Corps (Sialkot), the heaviest of the Pak Army Corps, posed a threat to the Pathankot-Jammu road and to Pathankot itself. It was important to capture the Shakargarh salient and reduce the crucial tactical disadvantage.

The offensive was launched along three axes

• Two striking southwards from the general direction of the Kathua-Samba stretch of the main Pathankot-Jammu road; and

• A third, subsequent thrust from the Gurdaspur area striking west-ward.

The operation started on the night of 5/6 December and lasted till the Ceasefire, culminating in the biggest tank battle of the war.

The two northern thrusts reached the outskirts of Shakargarh and Nurkot by 8 December —a very slow rate of advance due to extensive caution about enemy minefields laid in great depth.

The Pakistani forces had been expecting an attack in the Chawinda-Phillaura area. The enemy strength in the area was about one infantry brigade supported by a squadron of armour. As soon as the Pakistanis realised what the Indian were up to in the Shakargarh salient, they quickly and sent two armoured regiments (Pattons) from 6 Armoured Division to re-inforce the brigade in Shakargarh.

The Indian attack from the eastern side went in on the night of 8/9 December, across the River Ravi—supported, as were the other two, by armour and artillery. The western-most column reached the outskirts of Zafarwal. The Pakistanis reacted strongly and sent in an armoured counter-attack by two regiments of Pattons. However, the Indian Centurions quickly proved the superiority of Indian tank-gunners over those of the Pakistanis.

The 1965 story of Khem Karan was repeated in this battle — 45 Patton tanks being knocked out during the day and night long battle on 15 and 16 December. Indian Army’s losses were only 15 tanks.

Poona Horse, the Indian armoured regiment involved in this battle, had also fought here in 1965 (under the command of Colonel Tarapore, who was posthumously awarded the Param Vir Chakra) did well in the I Corps battle on the Phillaura front. The nick-name the enemy had given this regiment was “Fakhr-i-Hind,” the Pride of India.

After the tank battle, the three columns moved forward till they were in contact with the defences of both Zafarwal and Shakargarh. Here again, the Ceasefire came just in time to save the enemy from losing those two towns.

Rajasthan Sector

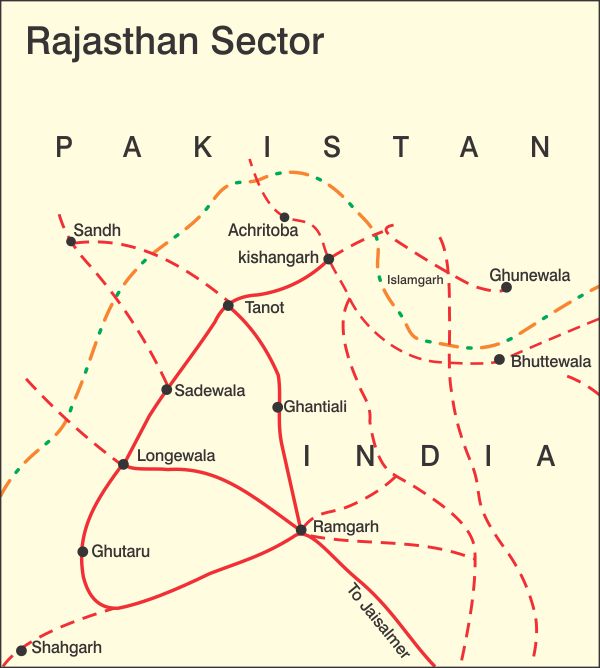

A Pakistani infantry brigade supported by a regiment of armour (mixed T-59s and Shermans) launched an attack on Indian positions at Longewala (Jaisalmer sector) — probably to disrupt an anticipated of a thrust by Indian forces – towards the road and rail link at Rahim Yar Khan. The soft vehicles of the supporting troops bogged down soon after crossing our border. The ranks too got stuck in the soft sand, providing easy targets for the IAF aircraft. One of the IAF Hunter pilots described it as a duck shoot. More than 20 enemy tanks were destroyed on the first day.

The next day the targets were the long columns of soft vehicles.

Southern Command Theatre

The intention in the Southern Command’s area of responsibility in Rajasthan was to force the enemy to commit his strategic reserve, ie, Pak I Corps, which included Pakistan’s 1 Armoured Division and an infantry division. It entirely succeeded in this aim.

Following the enemy’s failed attack at Longewala, Gen GG Bewoor, GOC-in-C Southern Command, struck out from the Jaisalmer sector to capture Islamgarh and, further south, along the old Bombay-Sind-railway axis, a more determined thrust towards Gadra.

Gadra was taken easily, while along the railway axis a brigade struck out for Khokrapar and beyond. At the same time, a whole series of long-range raiding columns were sent out into the salient between Nagar Parka and the railway axis. Special Forces dominated the area, liquidating Pak outposts and within a few days the whole salient was under Indian control. Meanwhile, the column along the railway axis forged ahead and laid sieging to Naya Chor, which was saved only by the Ceasefire.

The enemy reacted by sending 33 Infantry Division down from Pak I Corps to reinforce the Rahim Yar Khan-Hyderabad sector. The offensive-defensive strategy paid off.