When Joseph Chamberlain, the popular British statesman from the 19th Century, wrote his speeches, he most likely did not think that one of his phrases would become so popular that it would be coined “the Chinese curse” – an ironical expression, seemingly disguised as a blessing – “May you live in interesting times.” This phrase represented the time he lived in – a very volatile period, scarred by numerous wars, local conflicts and genocides, the fall of one of the largest empires and the beginning of the end of the empire he lived in.

The “interesting times” continued for a couple of decades after his passing and they included two world wars, hundreds of millions of casualties and a completely new social system, whose inefficiency to a large degree contributed to the casualties. Following that was a very quiet period, which, however, marked the time of the greatest gains and advances in science and technology that humankind has known. The doctrine of the open economies advanced extensively the existing fragile commercial relationships and that was one of the major factors, which allowed for growth in many economies across the globe.

Fast forward to recent times and we see a very different picture. Local conflicts are waged by traditional warfare, while competition among superpowers is far more strategic and involves economic measures to influence the trade of each market agent, which would then affect its economy and the likelihood to alter its diplomatic and military policy. The economic wars are nothing new and they involve any kind of government interference in the market, which would change the equilibrium price and consumed quantity.

Most often, it is achieved via tariffs or quotas, but sometimes they could be disguised as regulation, such as health standards, where the targeted side would have to incur time and effort, effectively increasing the average cost, to reach compliance. Of all, tariffs are the most straightforward and easy to implement as they require just a decision to impose tax on the imports from a specified destination. They effectively either increase the price for the local consumers or the cost of the importers if they can shift costs back down the supply chain.

Quotas are harder to implement, because they allow imports up to a specified amount. Easier said than done, this requires careful analysis to establish the amounts and later monitor and enforce it. Government bureaucracy in any country throughout history has proved that it is far less effective than markets in determining the consumed amounts and appropriate prices and the most obvious examples are all the communist countries in history.

Even though these instruments are part of protectionist policies, where the aim is to support the local economy, their use usually yields negative results. These markets get higher prices, less consumption and in the case of quotas – far stronger local monopolistic structures. One thing is certain though – when the imports structure is changed, opportunities are created for additional outside market agents.

According to data from the World Bank, the total imports of the US for 2018 were $2.41T (trillion) and China’s share of them was $499B (billion) or 20.7%. India’s share of that was nearly $52B or 2.16%. It is obvious that countries with the same population and comparatively equally open to the largest import market in the world share two very different fates. Strikingly, even though China is ideologically far more distant to the US, compared to India, it is enjoying 10 times greater market for its surplus than India. The benefits of this surplus could then be used to increase their military and diplomatic influence in the long term.

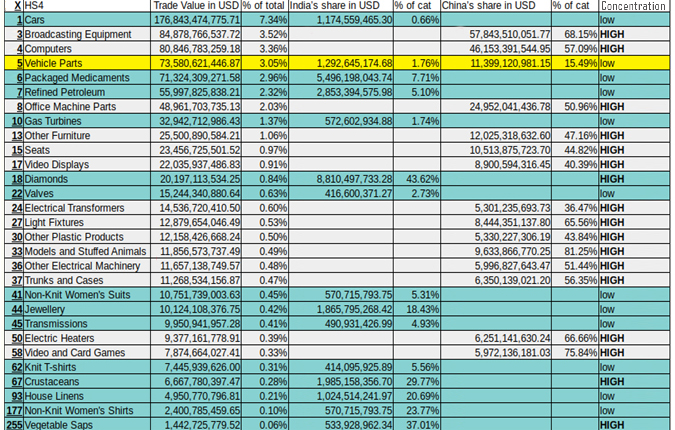

The composition of the US imports from both trading partners shows very interesting patterns and we can estimate relative dependence on each side, which is a crucial factor in trade and diplomatic influence. The USA’s share of exports for both countries is relatively similar – 16% for India and 19.3% for China. Out of India’s, three categories make up for a third of the total amount and 37 categories for 2/3rd. China, on the other hand, has seven categories that make up a third of its exports to the US and 50 for 2/3rd of them. This shows that China has noticeably better diversification in sectors and is less dependent. Out of US imports, China’s share is 20.7%, while India’s is just 2.16%.

The area of striking difference and source of greatest influence, however, is elsewhere. When we analyse the 15 largest categories of trade for both countries, we see that they have practically no overlap (competing only in vehicle parts, where China’s share is again 10x India’s, but their overall share is minimal). However, the imports from China are within the top categories for the US and their share is on average over 54%, while India’s dispersion is towards the middle and they make up on average less than 14% of each category.

This is easily illustrated in Figure 1. Column X (first column) shows the number of the category in terms of size from all US imports. For example Valves is the 22nd largest import category for the US, where India’s share of that is 2.73%. India’s rows are in blue, while China’s are in gray. The last column shows concentration based on 25% benchmark, i.e., a share of above 25% is considered high and important for the importer.

If we take a more qualitative look in the categories, we can see that those that China has concentrated in, have far greater importance for the US economy, thus, creating more systemic risk opportunities. Even though India’s largest export to the US is diamonds and it makes for 43.62% of the total imports in that category, it has zero importance towards future scientific advancement, information flow, R&D, allows for data collection or anything that pushes the boundaries of knowledge. This cannot be said for broadcasting equipment (networks), computers, office machine parts for a service based economy, video displays, electrical transformers and other electrical machinery.

The trade war so far has had detrimental effects on the US-China trade, but other countries benefitted from the vacuum created. India’s benefits so far were in the range of $1.2B and it might sound significant, but when we bring the other players in the picture, we see that there are, perhaps, many missed opportunities. Markets look for inefficiencies and alternatives are sought almost immediately. As a result Vietnam’s surplus was $2.8B, Taiwan’s $4.5B practically almost everything due to the disrupted supply chains in computers and network equipment, European Union $7B, Mexico $6.8B, Korea $4B, Japan $2.3B and Canada $2.5B.

The overview shows that China has positioned itself significantly better from a strategic point of view and can exert greater influence. The US has no choice at this point but to cater for it’s largest trading partner. After years of leniency and looking to the side from the Clinton, GW Bush and Obama administrations, this risk has finally been acknowledged by the Trump administration and the US took steps for future diversification and decrease of its dependency on China. The trade wars and the aftermath of the Huawei ban directly address many of the issues.

Significant change, however, requires long term effort. The good news for India is that it can start taking steps to become a preferred trading partner in the future in some of the affected categories. The US is taking not only economic steps to change the status quo. On 25 June 2020, while speaking at the Virtual Brussels Forum, Mike Pompeo, the US secretary of state, said that US troops are being moved to face Chinese threats to India and South-East Asia countries like Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines and the South China Sea. He further stated that the US military was “postured appropriately” to meet these “challenges of our time.” Bear in mind that Germany has the largest US base in Europe and is fundamental for its influence in the region.

Additional indication about the direction of the future US policy is his former statement of the formation of a US-European dialogue on China so that the Atlantic alliance (NATO) could have a “common understanding of the threat posed by China”.

It is clear that the US is shifting its policy and it is up to India to utilise the upcoming opportunities. It is in the US’s best interest to support everybody besides China in the South China Sea conflict. It is important for the supply chains feeding the US economy and they will be looking for allies on the economic and diplomatic fronts. India can adjust its foreign and economic policy for that. The diverted amounts from the China trade could increase significantly India’s macroeconomic policy, thus, affecting its entire economy. However, it has to concentrate in sectors requiring larger amounts of R&D and technological advances, because those sectors, in the long run, have significantly higher added value.

Ideologically and even culturally, India is closer to the US. It does not have such an expansionary doctrine and its economy, far more open to market principles, rather than lead by central planning by populist nationalists, and based on population twice that of the US and EU combined, can become far more appealing to the White House administrations in the future.

We live in interesting times and the economic, diplomatic and military relationships between the key powers of the world are changing. Whether the words by Joseph Chamberlain turn out to be a curse or a blessing is yet to be seen and it is up to the policymakers to use the created opportunities.