First Bloody Clash in 45 Years

The stand-off between India and China started near Line of Actual Control (LAC) in Eastern Ladakh, in May, after India started construction of new roads on its side of the border. New Delhi’s decision to boost up road and other infrastructure near the LAC did not go down well with Beijing and the latter upped the ante by sending more troops at four locations near eastern Ladakh and three in the Galwan Valley and one near Pangong Lake. Responding to Chinese aggression India had also moved an equal number of high-altitude warfare troops to these areas closer to the LAC to prevent intrusion of Chinese forces inside Indian territory.

The first official acknowledgment of tensions on the border came on May 10, when the Army issued a statement about clashes between Indian and Chinese patrols at two places. In Naku La in Sikkim, on May 9, a Chinese patrol on the Indian side of the LAC was confronted by an Indian patrol which led to a clash.

The Army also acknowledged a more serious incident that took place on the night of May 5-6 in the Pangong Tso lake area, during which soldiers from both sides were injured. On May 14, Army Chief Gen MM Naravane said that “both these incidents are neither co-related nor do they have any connection with other global or local activities”.

Chinese build-up began immediately after clashes between border troops in Ladakh and Sikkim on May 5-6 and May 9.

On May 29, President Trump announced that he had spoken to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who he claimed was “not in a good mood about what’s going on with China,” with regard to the “raging border dispute”. Trump also offered to mediate. India denied the talk had taken place, but both did, however, speak on June 2. The Indian readout mentioned that the two leaders had discussed “the situation on the India-China border”.

Extent of Intrusion

Defence Minister Rajnath Singh said, in an interview to a TV network, on June 2, that “Whatever is happening at present… It is true that people of China are on the border. They claim that it is their territory. Our claim is that it is our area. There has been a disagreement over it. A sizeable number of Chinese people have also come. India has done what it needs to do”.

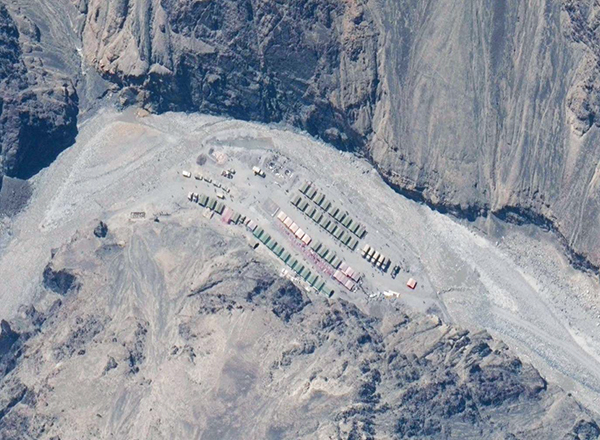

The most serious issue was in the area of Pangong Tso and its northern banks, where Chinese soldiers had moved up to the line they perceived to be the LAC. Satellite images showed that they had also undertaken some construction activities in the areas that were claimed by India.

In the area of Hot Spring, Chinese soldiers moved into three areas – PP14, PP15, and Gogra – backed by a large number of troops and heavy equipment on their side.

There were similar reports of a massive Chinese deployment on their side in the Galwan river valley area.

At each of these places, around 800-1000 Chinese soldiers had reported to have crossed over to the Indian side of the LAC, at distances of around 2-3 km. Tents were pitched by the Chinese soldiers in the area, along with a fleet of heavy vehicles and monitoring equipment. Chinese helicopter movement close to the LAC was also monitored by the Indian side.

Indian soldiers in equal numbers were deployed in the area, separated by a distance of 300-500 metres from the Chinese.

The Indian side was certainly taken by surprise. Chinese soldiers mobilised into areas where there has historically been no dispute. The Covid-19 pandemic led India to cancel its annual training exercise in Ladakh, which brings a brigade to the area to react quickly.

The Chinese, too, conduct a training exercise in the area every summer, and they diverted their troops for this mobilisation while the Indians had to scramble troops from elsewhere to respond.

There were reports of physical clashes and injuries to soldiers of both sides, which is in violation of various agreements and standard operating procedures (SOPs). But no shots were fired.

Military Level Talks

There were multiple rounds of talks at the level of local military commanders (Colonel- and Brigadier-level), and three rounds of talks at the level of the division commanders (Major General). Five meetings had been held between local military commanders of the two sides by 24 May, but the situation remained unresolved.

After these talks were inconclusive, Corps Commander-level talks were held on 6 June. The Ministry of External Affairs said that “the two sides will continue the military and diplomatic engagements to resolve the situation and to ensure peace and tranquility in the border areas”.

Lt Gen Harinder Singh, XIV Corps Commander, led the Indian delegation to the Chinese border meeting point at Moldo near Chushul. The Chinese army team was led by Maj Gen Liu Lin, commander of the South Xinjiang Military District, which is responsible for the border with Ladakh.

The Indian agenda for the meeting centred around restoration of the LAC status quo ante — before China diverted its forces from an ongoing military exercise towards the Indian side. The Indian side planned to raise the issue of the limits of patrolling by both sides, as conducted hitherto, and seek restoration. In the Pangong Tso area, Indian troops are not being allowed by the Chinese to patrol up to Finger 8, the LAC point on the northern bank of the lake.

India was also for a mutually agreed progressive reduction of heavy military equipment, such as artillery guns and tanks, from the rear areas of both sides.

Simultaneously, talks took place at the diplomatic level in Beijing and New Delhi.

Army delegations, led by Maj Gen Abhijit Bapat, commander of the Karu-based HQ 3 Infantry Division and his Chinese counterpart, met again on 10 June again to resolve the standoff. It was the fifth meeting between the two major generals. The two officers last met at Patrolling Point 14 near the Galwan area on 8 June as part of continuing efforts to resolve the confrontation.

The focus was on resolving the situation on the northern bank of Pangong Tso, which had been at the centre of the ongoing border scrap and where troops were still locked in a face-off.

Even in earlier instances of standoffs – Depsang in 2013, Chumar in 2014, and Doklam in 2017 – multiple rounds of talks took place at diplomatic and military levels before the deadlock could be broken.

Army Chief, Gen Manoj Naravane visited the Leh-based HQ 14 Corps to review the situation on 23 May. The top military brass briefed prime minister Narendra Modi on 26 May about the situation in Pangong Tso lake, Galwan Valley, Demchok and Daulat Beg Oldi where the Indian and Chinese troops were engaged in aggressive posturing.

Chinese President Xi Jinping ordered the military to scale up the battle preparedness, on 27 May, visualising worst-case scenarios and asked them to resolutely defend the country’s sovereignty.

The Bloody Clash at Galwan

On the evening of June 15, in the first deadly conflict in at least 45 years, 20 Indian soldiers, including the commanding officer of an infantry battalion, lost their lives and possibly 43 casualties were suffered on the Chinese side. China’s foreign ministry expressed ignorance, deliberately or otherwise about fatalities on either side. (See next article).

Prime Minister Narendra Modi convened an all-party meeting on June 19 where he said that though India is a peace loving country, it can give befitting reply if provoked.

A significant change in Rules of Engagement (ROE) by the Indian Army followed the Galwan Valley skirmish giving “complete freedom of action” to commanders deployed along the contested Line of Actual Control (LAC) to “handle situations at the tactical level,”

Post-Clash Meetings

Maj Gen Abhijit Bapat, and his Chinese counterpart held talks, on 18 June, at Patrol Point 14, which witnessed the seven-hour-long clash. This was the seventh meeting between the military officials. Since then meetings have taken place regularly as part of a phased de-escalation strategy to ease tensions that have persisted.

Corps Commander level talks were held again on June 22 at Moldo. There was a mutual consensus to disengage. Modalities for disengagement from all friction areas in Eastern Ladakh were discussed.

Gen. Naravane travelled to Ladakh for his second visit since the standoff began on 5 May.

Another round of talks was held, on 30 June, between Lt Gen Harinder Singh, GOC HQ 14 Corps and Maj Gen Liu Lin, Commander of the South Xinjiang Military District at Chushul. There was no breakthrough, but two sides agree to sustain tempo of dialogue to maintain peace and tranquility at border.

There had been no progress on the consensus and modalities of disengagement agreed on 22 June. A consensus had been reached on 6 June was well but was breached with the violent clash at Galwan valley on 15 June.

Discernable Pullback

The two sides agreed to a phased pull back in a three-step process. They would focus on de-escalating the present deployment of war-waging weapons and thousands of troops. Before entering the second stage, the two sides would physically verify the ongoing process of creating a 3-km buffer zone at the LAC between the troops of both sides. The process started on 6 July.

By 10 July, disengagement had successfully been completed in the Galwan Valley, Hot Springs and Gogra areas. While the PLA pulled back 2km from Patrolling Point 14 (Galwan Valley) and PP-15 (Hot Springs), a similar retreat was completed at PP-17 (Gogra). The Indian Army, too, pulled back proportionately in these friction areas.

The Finger Area at Pangong Tso was where negotiations were dragging on as the Chinese troops had dug in their heels in Finger 4. The Finger Area, which refers to a set of eight cliffs jutting out of the Sirijap range overlooking the Pangong lake, remained the biggest test and hardest part of the disengagement process.

The army was keeping a strict vigil along the contested border in the Depsang sector where the PLA’s forward presence was a matter of serious concern and where a 2013 Chinese intrusion blocked the access of Indian soldiers to several patrolling routes, including the ones leading to PPs-10, 11, 11A, 12 and 13.

[…] ALSO READ INDIA-CHINA: Chinese Intrusion in Eastern Ladakh […]